The last time that Lee Soon-nyeu saw her father, he was being led away in shackles.

It was 1950, weeks after North Korean forces had invaded South Korea. Soldiers had detained her father, who worked in the South for the government, while he was out fishing and were torturing him at a local millhouse. She says she started selling fruit nearby to try to catch a glimpse of him.

After a few days, he finally reappeared.

“I saw 14 prisoners chained together in twos there. My father was at the end of the line,” she recalls. “I called out ‘Father!’ and he looked back at me. His face looked yellow and was swollen. He didn’t call my name. He didn’t answer at all. That was the last time I saw him.”

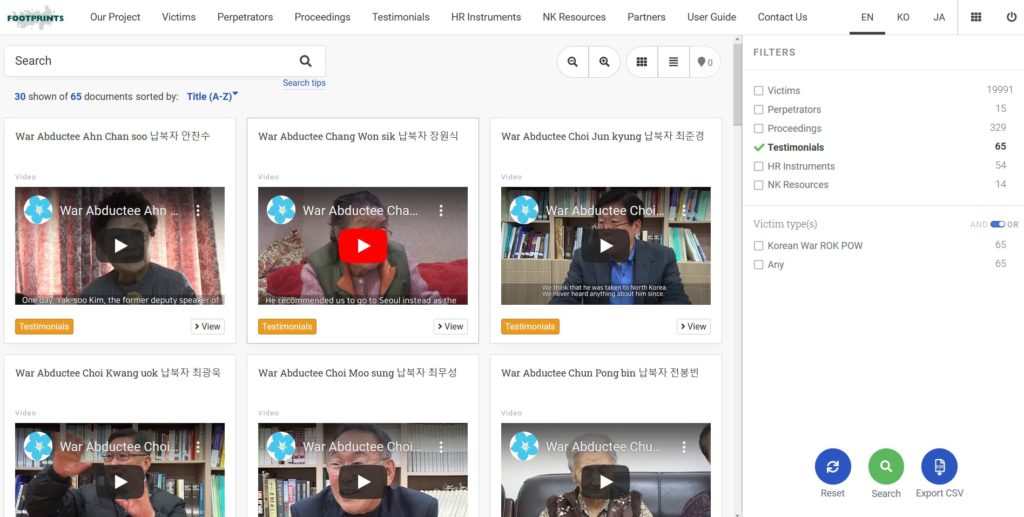

Lee Soon-nyeu never found out what happened to her father, Lee Ki-ryong. Her video testimony is one of many that are available in a new database called Footprints, which compiles cases of arbitrary detention, abduction and enforced disappearances committed in and by North Korea, stretching back to just before the outbreak of the Korean War.

The collection is the product of the Transitional Justice Working Group (TJWG), a Seoul-based NGO, in partnership with several other local family associations and human rights groups. HURIDOCS also supported the creation of Footprints, which is built on our flagship platform for organizing human rights information, Uwazi.

Footprints is intended to be an important piece “in the mosaic of transitional justice,” says Ethan Hee-Seok Shin, a case researcher for TJWG. The hope is that it serves as a resource for family members, journalists, advocacy campaigners and lawyers in South Korea and beyond who are working towards a resolution for these human rights violations.

“It’s very important that these issues are not just forgotten,” he says. “We have a responsibility to the extent possible to make sure that the victims find remedies.”

“It’s not just statistics. It’s people with stories.”

A decades-long history of abductions

Footprints currently holds more than 19,000 files on wartime abductees, which represent a quarter of the estimated number of civilians who were taken by North Korean forces during the 1950-1953 period.

But the abductions didn’t stop then. According to official figures, 3,835 South Korean individuals have been abducted since the end of the war, most of them from fishing vessels at sea. A little over 500 of them have never escaped or been returned. This figure includes 11 passengers and crew who were aboard Korean Air Lines flight YS-11, which was hijacked in 1969.

The database includes entries for these postwar abductees. It also contains several dozen cases of arbitrary detention of people within North Korea as well as the forced repatriation of North Korean escapees, mainly by Chinese authorities.

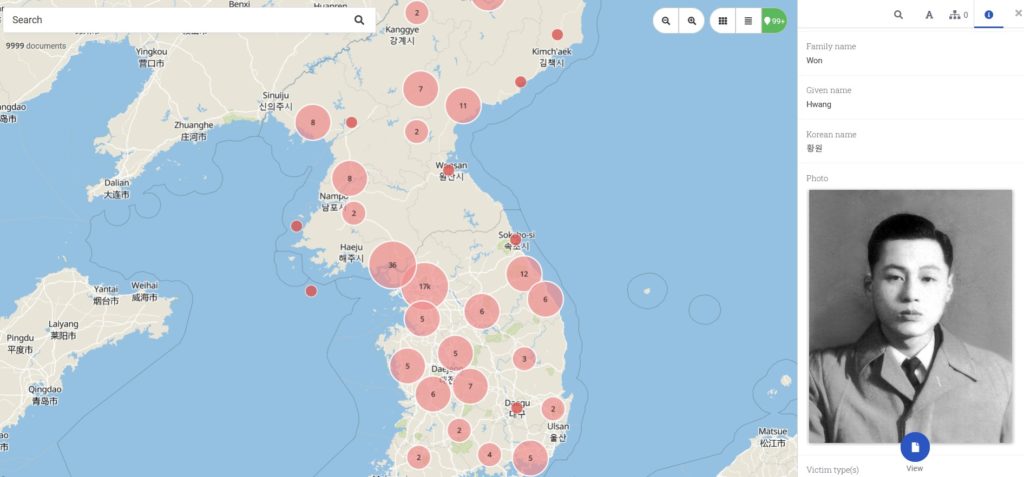

No matter the circumstances of the case, entries for each victim feature basic personal details, what state agency perpetrated the abduction, and related photos, news articles and reports (when available and appropriate). Furthermore, they document the locations of where the victims were last seen, where they disappeared or were abducted, and where they are detained.

Beyond case files, Footprints also compiles documentation from legal proceedings on the topic; relevant human rights resolutions, treaties and mechanisms; and various reports on the human rights situation in North Korea.

With so much information to house in one place, it was tricky to figure out how to organize it all, says Ethan. The chosen model had to not only accommodate existing data, but also work well with future data — these human rights violations, unfortunately, still occur.

It was a fruitful challenge for our team at HURIDOCS, too. “Working to support the Footprints database was an incredible learning opportunity to understand and appreciate the unique use cases of different organizations and how they are continuously shaped by their contexts,” says Natasha Todi, the HURIDOCS programme officer who helped TJWG to shape the Footprints collection.

“The attention to detail and the careful consideration when creating the data structure has provided a foundation for a definitive repository for lawyers, students and researchers.”

“I can’t ever forget how you were unfairly taken away from us”

Although the situation surrounding North Korea has its unique difficulties, some of the hard-won lessons to come out of the Footprints experience — about managing a project and organizing a large collection of information — are applicable more widely.

TJWG plans to pay these forward through Access Accountability, an initiative that provides advocacy groups around the world with training and resources on human rights documentation.

“These tragedies happen in other countries as well, so perhaps in the future it might be possible to have Footprints for other countries with human rights violations,” Ethan says.

Closer to home, Footprints represents one of the first concerted efforts to pool data among the various organizations that work on cases of people taken in and by North Korea. The partners who have contributed information and materials to Footprints include:

- Citizens’ Alliance for North Korean Human Rights

- The Korean War Abductees Family Union (KWAFU)

- Justice for North Korea (JFNK)

- 1969 KAL Abductees’ Families Association

- Mulmangcho

- No Chain

- Family Union of Korean POWs Detained in North Korea

In fact, this is an important goal of the Footprints project, says Ethan: to break down the silos that divide allies and create synergy in their advocacy efforts.

Some of the partners have been at this work longer than others. But be it seven years or 70, the pain of not knowing what happened to a missing loved one is something that endures.

By the time that Lee Soon-nyeu recorded the testimony available in the Footprints collection, many decades had passed since her father’s abduction. Her anguish, however, remained.

“I want to see you the more I think about you,” she says. “I can’t ever forget how you were unfairly taken away from us. Father! Help me find you so I can help you rest forever in a comfortable place.”

The road to justice is long and winding. We at HURIDOCS hope that the Footprints database represents a positive step in the direction of resolution.

Do you have a collection of human rights cases that you need to archive? We’d love to help. Get in touch.