When she left Palestine in the 1980s after five years to take up a post in an inner city high school in Winnipeg, Canada, she almost left her work behind. Eventually, Judith Dueck did decide to take it with her even though it seemed like she was entering a new phase of life. Thanks to her early work and ongoing opportunities, she embarked on a challenging journey to develop standards for the documentation of human rights as part of an international task force. More than twenty five years on, in this interview – part of the series to commemorate HURIDOCS’ 30th anniversary – Judith looks back at her engagement for systematic and powerful documentation tools and the exciting changes and new people that the advent of technology brought to the human rights community.

Your work on developing international standards for the documentation of human rights violations is still relevant today. What were the challenges that the task force you were part of had to overcome in developing them?

Our intention was to design a system that would cover most of what would be needed by human rights organizations, but flexible enough so that organizations with a particular focus, could select specific relevant aspects for use. Based on this, we developed the Standard Formats, Microthesaurii and the matching computer programs: Evsys, WinEvsys, and finally OpenEvsys. Other organizations used them as well to develop their own programs.

We had micro and macro challenges. On the macro level, the comprehensiveness of the tool seemed too complex or difficult for some people to understand. On the micro level—there were many debates about terminologies for describing details about people and events. In some cases, we could borrow already established terminologies from other organizations like the ILO or the UN, but often we had to develop our own standardized coded vocabularies.

This really was a long and sometimes difficult process, but for me it also was an exciting experience to see how international collaboration can lead to results with such long-lasting impact.

How did you get involved with this? When and where did you first come into contact with HURIDOCS? What initially attracted you to the organization?

In the 1980s, I was living in the West Bank working as the administrative director of Al-Haq, a Palestinian branch of the International Commission of Jurists. It was clear within our context that we needed to devise a method of systematically keeping track of what was going on in the various communities and what was happening to specifically targeted victims. We wanted to track particular perpetrators and follow what they were doing. We had many paper files collected by our international and local staff including field workers in the West Bank.

We were a relatively new organization working at developing systems to retain the knowledge of these workers. Sometimes when staff leave, the knowledge in their head goes with them. This can lead to critical information loss especially when human rights are most under attack.

By 1986, a colleague of mine, Jonathan Kuttab, who was a founding director of Al-Haq, was part of the HURIDOCS continuation committee. He was aware of the power of this information and was equally concerned about the possibility of knowledge loss. He invited me to a HURIDOCS conference in Rome.

A lot of times people from outside the information management community have trouble understanding how managing information impacts the human rights world. Even as a concept it can often go over one’s head. How did Jonathan explain HURIDOCS to you?

Jonathan told me that HURIDOCS sought to develop the tools needed to harness information to empower human rights work. I immediately understood since these were issues Al Haq also wanted to address. The conference proved to be a perfect occasion for interaction with others who also had this concern.

What happened at the conference and what led you to become so involved afterwards?

In Rome, I joined the conversation about the need for a standardized system for organizing human rights information. In fact, one of the early mandates of HURIDOCS was to establish such a system for documenting human rights violations. At that time they had already developed tools for libraries, but they didn’t have tools for information about ongoing violations, where the information can have different or evolving interpretations due to differing perspectives, new developments, and changing environments.

Before I knew it, I was assigned to be a task force leader to develop such a system. However, finances were limited and the project remained in the conceptual stage. One year later in 1987, my term ended at Al-Haq and I returned home to Canada. In fact, I almost left my personal documentation resources and materials behind, but at the last minute, decided to throw them into my suitcase thinking—who knows what future holds? Once home I was appointed teacher-librarian in an inner city school.

So did your materials become useful after all? When was that?

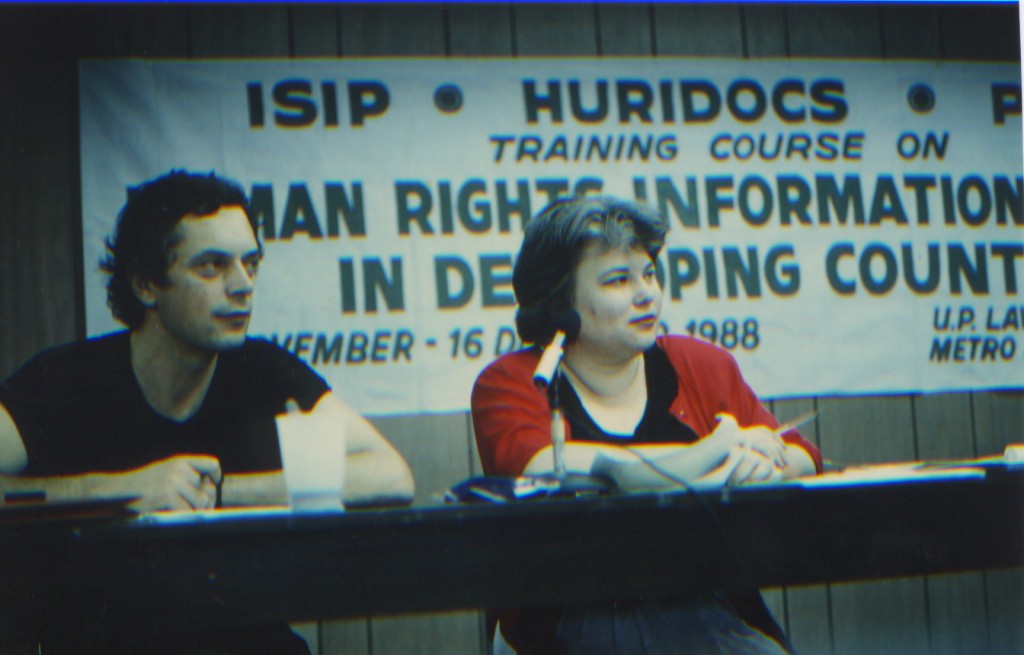

One day in 1988 I received a call from Hans Thoolen, one of HURIDOCS’ founders, inviting me to present my ideas and practical experience at the Society for International Development Conference in India. At the conference there was considerable enthusiasm around the idea of creating a standardized system for documenting human rights violations and we established a worldwide task force. We held a series of meetings in various locations to consult a wide range of people, including Amnesty International, NGOs in Argentina, Chile and the Philippines along with many others who had particular expertise. It was a challenging opportunity and all of us were volunteers.

The project was constantly developing. Input from users and others enouraged change and development, not only to the terminology, but also to the structure. The first edition and computer program had been a standard, flat database. The second one was a new relational database called WinEvsys. The relational aspect was a very important change.

How did you discover that it needed to be relational?

Well, as we looked at the fact that a victim often had several perpetrators and a perpetrator often had several different victims and operated in several different contexts. We realized that we had to make allowances for those one-to-many and many-to-one relationships, which a flat database could not handle.

So, the tool was being continuously developed at the same time that it was being used by organizations. Did you learn anything else that impacted the system’s development as you went along?

We needed to develop a system which could make a record of history as it happened; use an indexing method so that information could be retrieved even years later; document the situation of a particular individual whether perpetrator or victim; and track incidents in a particular refugee camp, community, organization such as newspaper office, school or human rights organization. As it evolved, it also became obvious that statistics and observable trends would be highly valuable. And matching information formats to organizations who receive such information in the form of complaints or reports would also be useful.

This led to a significant debate about the use of all this information and its security—were we looking for a large database where everybody sends their information for everyone to use or were we aiming for a database that will allow organizations to do their own work sharing it when appropriate? One of the major considerations was protecting the privacy and the security of the individual. For example, if the wrong information became widely available, it could result in dire consequences including death. This conversation went on for a couple of years. Ultimately, we opted for leaving organizations in charge of their own information and helping them work with the tools themselves so that they could organize their own information in the way that was necessary for them. This goal has been reached in part in particular networks such the Coalition against Trafficking in Women in the Philippines. The standardized use of terminology, formats and computer programs also allowed for exchange or merging of information. However, enabling the exchange of information between networks still remains somewhat of a challenge.

Do you feel that HURIDOCS, as an organization or as a concept, was an innovation for the human rights world?

Absolutely. I would most definitely say that HURIDOCS was ahead of its time and very innovative in finding ways of organizing information for human rights. For example, Martin Ennals, the founding HURIDOCS president, a dedicated human rights activist and the first Secretary-General of Amnesty International, was an exemplary visionary. When he would talk about organizing and standardizing information on human rights for effective exchange and advocacy, it sounded like he was talking about a computer, but there weren’t any in common use back then in the 80s. So, yes, HURIDOCS was visionary, but it was also born out of practical needs. And that makes HURIDOCS quite exceptional.

HURIDOCS’ former chair Kofi Kumado spoke once about “getting bitten by the HURIDOCS bug.” What does this mean to you?

I suppose the “bite” for me was at that first Rome conference. And there was no antidote. So, I just became more and more involved. The HURIDOCS network includes many wonderful, committed people. Working with the task force, the continuation committee, training participants, staff, volunteers and others has been enriching. For me, what I find so inspiring is that many of these people come from difficult situations and have had difficult personal experiences. Some of them have been in prison or have been victims themselves and it was an honor to be able to meet and work with them. So, I think the common goals of HURIDOCS and working together was a big draw for me and for many others.

Do you think that new technologies and developments in the human rights world over the years have opened up the HURIDOCS community to new kinds of people?

I would say that a much wider range of people are involved. Initially, we were aiming at administrators of organizations because they made the decisions and also documentalists because they developed and used the tools. Now I would say technicians, IT folks, communications, academicians, and statisticians all play a role, but library scientists and administrators are still key because their involvement is critical for the successful implementation of new tools and practices.

Before we were all human rights people, not “techies” , but as our ideas developed we needed technical expertise to realize them—for example, we needed programmers for HURISEARCH and OpenEvsys. They may have had experience working with human rights organizations, but they weren’t necessarily human rights workers in their work life. So, there are people who may not fit the usual human rights mold—if there is such a thing—but they are interested in contributing in their own way and have the skill sets necessary to build the tools or assist in others ways. Interns and volunteers with a variety of skill sets are an invaluable and critical part of the HURIDOCS community.

Judith Dueck is an award-winning career teacher, librarian and writer who has developed human rights education units in Canada’s public school sector. Most recently, Judith was the Director of Research Content and Scholarships for the Canadian Museum of Human Rights in Winnipeg, which is due to open in 2014. Among other accomplishments, Judith was Al Haq’s administrative director (West Bank branch, International Commission of Jurists) in the 1980s. She also led the initial development of the TANDIS project for the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Judith served on HURIDOCS’ board from 1992 to 2009, being vice chair from 2002. She chaired the HURIDOCS’ task forces and co-wrote the Events Standards Formats and Microthesauri, two tools aimed at standardizing the way in which human rights violations are documented and the language used to describe violations. She also played an important role in the creation of HURISEARCH, HURIDOCS’ human rights search platform. Since serving on the board, Judith continues as a member of the HURIDOCS international advisory council. She leads seminars on documentation, human rights and educational methodology. She sits on ILGA Europe’s board to jury the Documentation and Advocacy Fund (International Lesbian and Gay Association). Judith has written books and articles including the award winning book, Not in our Schools on the topic of censorship. She recently co-wrote the lead chapter in Human Rights and Information Communication Technologies: Trends and Consequences of Use, which was released in July 2012.