Challenges in accessing human rights information are a significant problem for advocates. But they are also a problem for human rights bodies (the information producers) because these barriers impact their ability to realise their promise for those who promote and protect human rights. There is no standard collection of documents for information on international human rights standards or their application to particular rights violations. Nor have human rights bodies themselves adopted consistent or comprehensive approaches to sharing information.

This is a big problem. Human rights defenders (and oversight bodies) around the world need this information to frame and support their legal arguments, know what policies and recommendations States support at international bodies, guide their strategic decisions, understand realities on the ground, and be successful in protecting human rights. Despite this need and new technology available today, these defenders continuously run into frustrating technical challenges when trying to find and share information. Here are a few of the big ones that we are most familiar with:

Challenge 1: Information is not published with users in mind.

Too little thought is given to what information people need and how they would want to find it. Publication follows the logic of the institution, not of those who need information. Here are just a few examples:

Example 1: Accessing cases at the Inter American Human Rights Court and Commission

Any human rights lawyer could tell you that it’s helpful to be able to find all the documents (decisions, appeals, etc) related to a particular case. But, before CEJIL built their online case law database, someone researching a case from the Inter American Human Rights system would have to go to both the Court and Commission websites, and then look in two different places on the Commission website (one place for decisions, one place for appeals).

Furthermore, on the Commission website, if you want to find documents on a case referred to the Court, you will have to know exactly what document you are looking for, including the type of decision and the year in which it was published because this is how they are organised on its website (by type and year). This greatly limits the ability for anyone without expert knowledge of these documents to find what they are looking for.

Example 2: Accessing the UN Human Rights Council resolutions

The UNHRC drafts resolutions during each Council session. The final resolutions are published 6 to 8 weeks after the respective session. As you can imagine, some advocates need information on these resolutions sooner than that, so the Council offers access to these drafts immediately the session. The problem is, you need the password to log-in to their extranet to access these documents.

Example 3: Finding treaty body jurisprudence

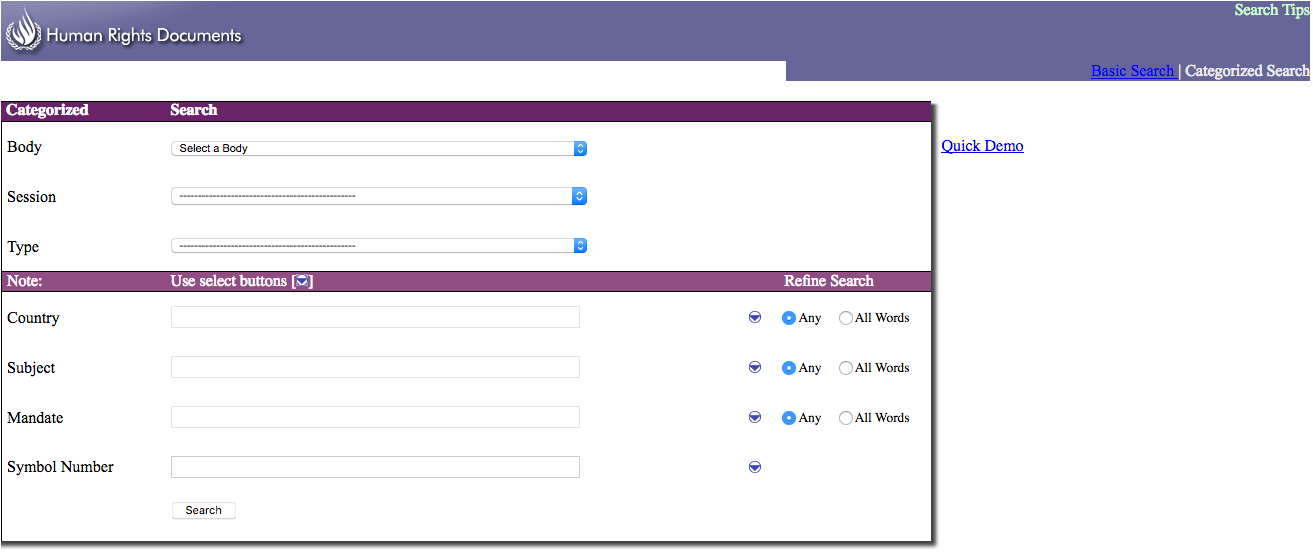

If you’re looking for jurisprudence of a UN human rights treaty body (the Convention on the Rights of the Child, for example), which database should you use:

What is the difference between these databases? Do they access the same information?

Furthermore, most of the UN databases and the Inter-American and African bodies’ websites don’t allow users to use text or keyword search within decisions and other documents. Instead, the user would need to know specific information about the document in order to find it, such as year, type of decision, etc.

Finding jurisprudence is so difficult that even members of treaty bodies themselves see it as one of the biggest problems affecting their work, as highlighted in a recent May 2018 report by the Geneva Academy (p 28):

“TB members are not always familiar with other Committees’ jurisprudence or even the past decisions of their own Committee. Better information flow could therefore enhance the work of individual TBs, help unify their jurisprudence, and improve their coordination. To achieve these goals, a more accessible and user-friendly database of TB jurisprudence seems essential. The Venice Commission of the Council of Europe provides a model: its information sharing and online communication between sessions have made its work more available and better known.”

Ultimately, the inability for human rights actors to find information on States’ human rights records via these documents and resolutions, shields states from much-needed scrutiny.

Challenge 2: Information is not published with re-use in mind.

The documents published by human rights bodies are jam-packed with interesting, useful, and actionable information. When this information can be easily re-used by defenders and human rights bodies, it can reveal important patterns and connections, helping to break down silos. When information is shared in this way without metadata, raw data, versioning information, etc – it significantly limits the ability for defenders to analyse the information in a way that’s most useful for them. Here are a few examples:

Example 1: Actionable UNHRC data is buried in PDFs

In order to see something as basic as the voting pattern of a Human Rights Council member, someone would have to manually find and compile that data from each document.

Example 2: Tracking references between decisions must be done manually

To understand how legal human rights precedent spreads and strengthens throughout the African Human Rights System, it is important to be able to see which decisions are referencing previous decisions, in what ways, and how many times. For example, you may want to know: how many times has the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights referenced decisions made by the Committee on the Welfare of the Child? Or you may want to know if a decision or judgment is still “good law” by being able to determine if it continues to be cited by the relevant body (or if the holding has been subsequently modified in later decisions). Information on these references should live with each document as metadata and should be easily accessible, but human rights bodies do not yet make this information available in a usable format.

How do we address these challenges?

What are the existing recommendations and frameworks within which to engage these human rights bodies, co-create open data principles, and put these principles into practice?

In August of 2017, David Kaye, the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, submitted his Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression. In it, a key recommendation is to setup access to information policies that include in “in particular proactive, clear, searchable and secure disclosures” (A/72/350, para. 31 and 32):

“31. Requests for information should be a necessary fall-back position in any access-to-information policy. At the foundation of such a policy, organizations must actively disclose information that is likely to be of relevance to the public, and they should do so on a timely basis, including consistent and usable updates, especially of websites […]

32. Public disclosure should also involve the following points: first, the institutions themselves should engage on a regular basis with members of the public, typically through civil society organizations, to ensure that they are making public all relevant and valuable information. […]”

This report, along with submissions from NGOs like the International Service for Human Rights, are important for documenting these issues related to access to information, and provide appropriate, achievable recommendations. The next logical question is – how are these recommendations put into practice?

We know that it will require an increase in resource allocation. Existing technology and communications teams are overworked and don’t have the space, resources or mandate to initiate new ways to improve these systems. These large organisations are moving too slowly on both fronts which is effectively outsourcing the problem-solving to NGOs like UPR Info, CEJIL and IHRDA, who invest immense labour to address these sectoral challenges.

But we also know that it will take a shift in how these institutions see the role and responsibility as information producers. Human rights bodies must have an increased commitment to transparency and the public’s right to information. Some bodies don’t even bother to upload all their decisions, reports, or press releases – or do so belatedly. So, how do we in the human rights community push for and enable this shift in institutions?

Perhaps this is an area that we could learn from other sectors, such as the Open Government Data movement. Open data is digital data that is made available with the technical and legal characteristics necessary for it to be freely used, reused, and redistributed by anyone, anytime, anywhere. The UN is in fact an Open Data Standards Steward which assumes a commitment to the Charter Principles.

So what is missing in order to make these principles and recommendations a priority? How can we do a better job of advocating for improvements? What can we learn from the Open Government Data movement in enabling environments, cultures, and initiative to make this happen? What would it take for human rights bodies to share their information in line with these principles?

We will be discussing these challenges and sharing ideas for addressing them at RightsCon this week so please come to our panel on this topic on Thursday to learn more!