“For as long as I’ve been building web apps, it’s been apparent that most successful websites are communities – not just interactive pages, but places where groups of like-minded people can congregate and do things together.”

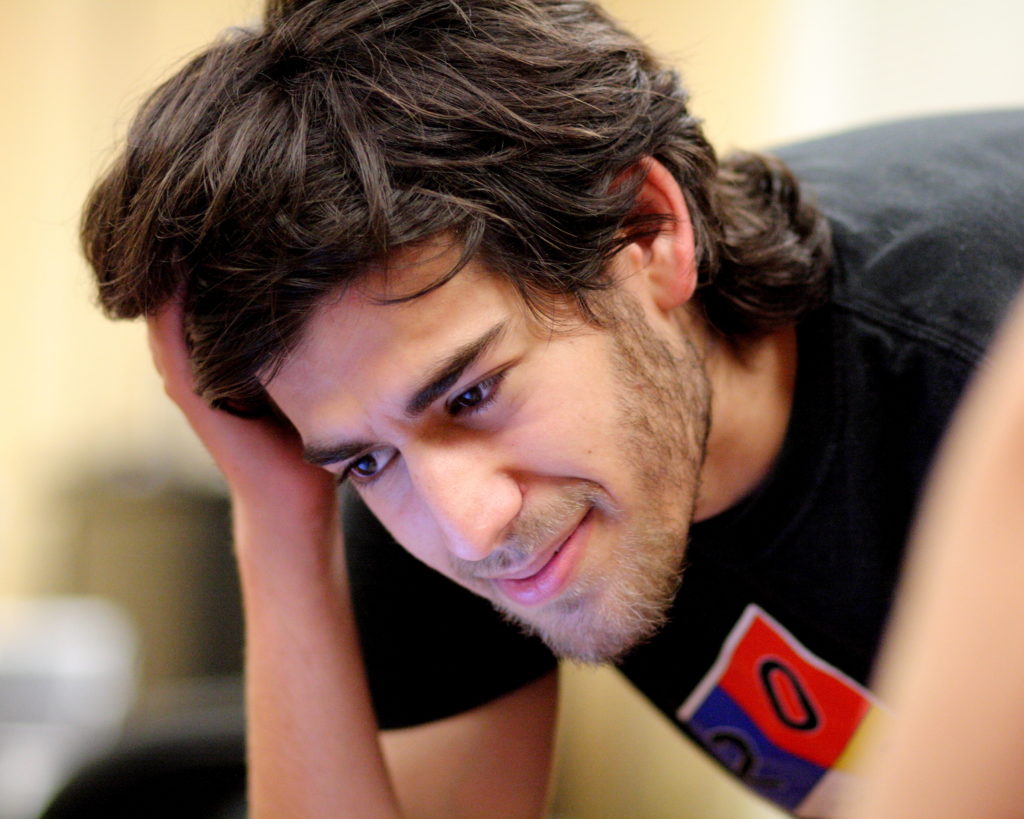

– Aaron Swartz, A Unified Theory of Magazines (September 2006)

Aaron Swartz was committed to make the world a better place. He fought for open and accessible knowledge and for the internet as a free and uncensored space that facilitates collaboration and information sharing. He combined political activism with technological skills and his passionate writings about politics, science, technology and learning inspired people all over the world.

In memory of Aaron Swartz, the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives (OSA) initiated the Aaron Swartz Fellowship to support activists, technologists and researchers who fight information control by governments, challenge information management practices in libraries and archives, and develop technological tools to make data and knowledge broadly accessible.

I am pleased and honoured to have received the 2018 Aaron Swartz Fellowship and spend three months at OSA in Budapest. The goal of my fellowship project was to support human rights defenders in extracting information from large collections of documents. The project builds on the experience of HURIDOCS, which for more than 35 years supports human rights organisations in their information management challenges. Connecting these challenges resulted in the development of Uwazi, an open-source software to structure, analyse and publish document collections.

The problem I set out to tackle

Metadata is a crucial when working with documents. The title, date, and topic help us to effectively filter and analyse a collection. Furthermore, semantic information such as discussion results, descriptions like the age of involved person, related organisations and summaries provide valuable insights at a glance.

Normally, the extraction of metadata from a large and unorganised collection is a very tedious and time consuming process: a person has to go through each item, detect the relevant information in the text and manually add it as metadata. If, after a first analysis, an organisation wants to further investigate another aspect, this manual iteration process through the entire collection has to be repeated.

Small non-profit organisations often struggle with organising and analysing data due to time constraints and lack of resources.

I started working with HURIDOCS in 2016 to work on this problem using machine learning, so we already had a good start on integrating sentence classification into Uwazi (you can read more about it in this blog post). The way it works is that by highlighting sentences that are relevant for a specific research purpose, a user starts training an algorithm – the algorithm then learns to identify underlying patterns and suggest related phrases.

But the problem we kept running into was that in order for the algorithm to learn well and to provide helpful suggestions, the algorithm needs a lot (think: thousands) of sample sentences.

We decided to tackle this problem with the support from the Aaron Swartz Fellowship. My goal was to build a customisable and flexible way for human rights defenders to extract metadata from their document collections, without requiring all the time and effort that goes into training the algorithm.

Identifying and implementing the solution

During the Aaron Swartz fellowship we were able to significantly improve the algorithm training process. By integrating the universal sentence encoder, providing only one sentence is enough to search for similar content and based on that content, train the machine learning algorithm. This is a powerful approach that goes beyond a text search. A high-dimensional representation of words enables the algorithm to detect morphologically, contextually and semantically similar phrases.

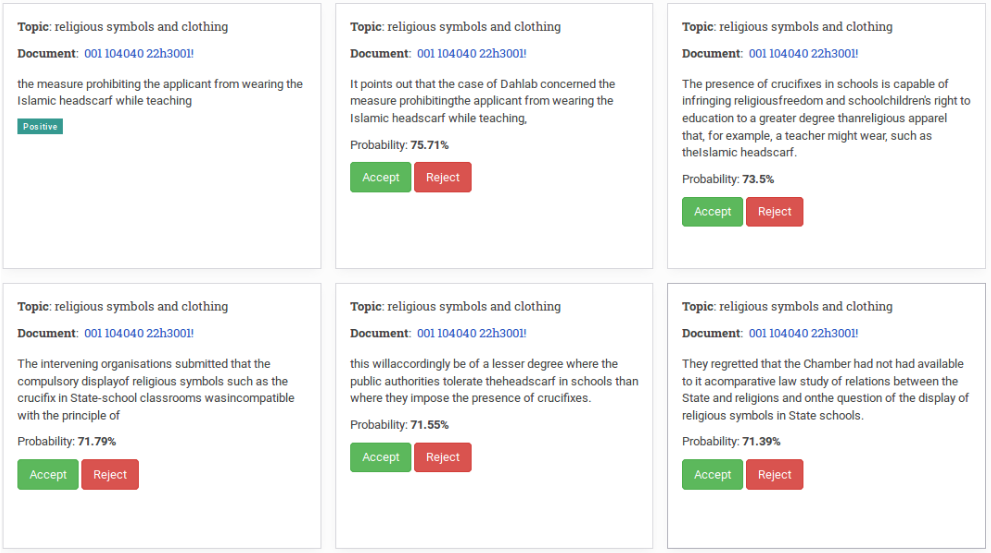

Consider this example (Figure 1) : a user wants to detect all documents that relate to the topic religious symbols and clothing. Highlighting the phrase ‘the measure prohibiting the applicant from wearing the Islamic headscarf while teaching’ yields sentences with semantically similar content even though the wording is different. The algorithm is able to associate the word teaching with schools and Islamic headscarf with religious symbols and even identifies crucifixes as related symbols in Christian religion.

By accepting or rejecting suggested sentences users can customise the algorithm to their specific research purpose.

When integrated into Uwazi (hopefully very soon!), this automated metadata extraction provides a powerful way for human rights defenders to analyse and understand a large (or small) collection of documents. Even though there is a long way ahead, non-profit organisations can access and make use of the benefits of machine learning to help advance their cause one step at a time.

This is only one example of what we achieved with support of the Aaron Swartz Fellowship. For more information have a look at my fellowship report.

My time in Budapest was a very inspiring and productive. I met amazing people with diverse backgrounds and had the chance to learn a lot about the processes in an archive and the workflow of researchers. I am very grateful for the Aaron Swartz Fellowship as an opportunity to learn and to grow and I want to thank everyone who contributed to this unique experience.