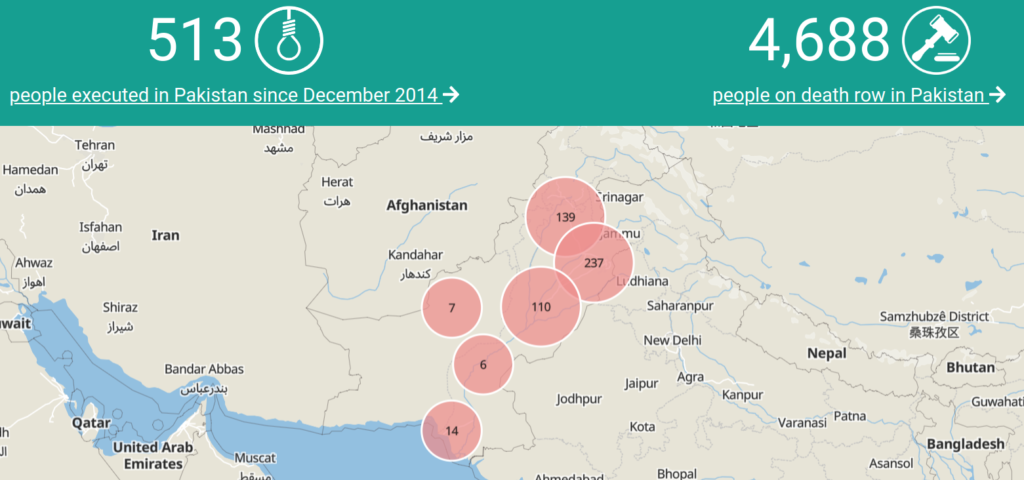

One in every four people sitting on death row throughout the world is in Pakistan. Globally, every eighth person executed is a Pakistani citizen. A total of 4,688 prisoners are awaiting execution in the country, many of them representing vulnerable populations, such as juveniles, individuals with disabilities or mental illness, and those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

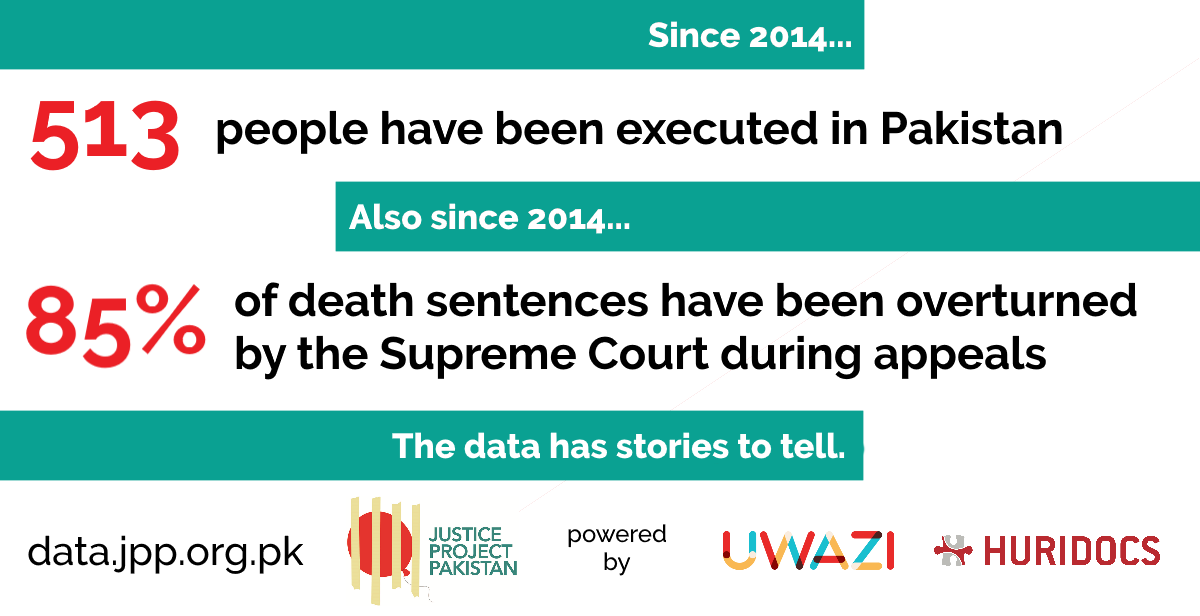

Over 33 crimes merit the death penalty and the rate of wrongful conviction is high, with 85% of death sentences struck down by the Supreme Court during appeals primarily because of flawed investigations.

Data on Pakistan’s use of the death penalty, compiled by our partner Justice Project Pakistan, paints a distressing picture of the country’s criminal justice system—and makes an effective case for reform. That data is now publicly available so that anyone calling for change can ground their advocacy and research in accurate information.

With support from HURIDOCS, Justice Project Pakistan launched their Death Penalty Database on 29 June 2019. Powered by our web-based platform Uwazi, it brings together details about current death row prisoners and the 513 prisoners who have been executed since 2014. That’s the year when Pakistan lifted a moratorium on capital punishment following the massacre of mostly children at a school in Peshawar.

Visit the Death Penalty Database >>>

In-depth analysis and interactive visualisation

The database also features an interactive map; visualisations of changes in the death row population and the number of death sentences and executions over the years; publications with in-depth analysis and context; and links to relevant news articles.

The data shows how the province of Punjab accounts for a disproportionately high percentage of executions. It also highlights how the majority of executions overall are not related to terrorism charges, despite terrorism being the original justification for abolishing the death penalty ban in 2014. In fact, users searching the database won’t find empirical evidence that capital punishment deters terrorism or crime—simply because it doesn’t exist, according to Justice Project Pakistan.

Acquittal comes too late

What they might encounter while digging through the collection, however, is the file for Kanizan Bibi, who suffers from severe schizophrenia and has spent the last 28 years on death row. From a poor background, she was convicted of killing her employer’s family while working as a housemaid, although she has long maintained her innocence.

Or the record of Ghulam Qadir and Ghulam Sarwar, two brothers accused of murdering Qadir’s daughter and son-in-law. They were eventually acquitted by the Supreme Court, but the news came too late—they had already been executed the year before.

When it comes to the death penalty, there are plenty more cases to examine, connections to be made, and trends to identify. The database aims to equip journalists, researchers, campaigners, policy makers and others to do just that.

Advocacy based on data is more effective

“Data-driven advocacy is [a] far more effective method than old-school diplomacy as it is based on objective, verifiable facts,” explains Justice Project Pakistan. It also “magnifies personal stories; the numbers are easier to organise; it identifies solutions, not problems; [and it] is poised to bring change faster.”

HURIDOCS assisted Justice Project Pakistan to define their strategy for the database, develop their open-source datasets, and customise Uwazi to suit their goals.

Well-organised information like the Death Penalty Database can surface critical patterns and compelling stories that otherwise would have remained in the shadows. Do you have a collection of documents that could support your human rights advocacy, if only it were more accessible? Get in touch!