Denial of education. Poverty. Violence. Forced marriage. Lack of clean water and sanitation facilities. Discrimination. Deprival of healthcare and well-being. Disregard of dignity.

These violations of basic human rights affect far too many people on the planet today, but one group is particularly vulnerable to these challenges: girls. Marginalized for their age on one hand and marginalized for their gender on the other, girls bear the brunt of a world that has yet to achieve gender equality and respect for children.

And to make matters worse, the international legal frameworks that should be protecting and promoting girls’ rights often don’t even mention girls, let alone articulate how their rights need to be explicitly implemented. Gender-neutral and age-neutral approaches are shaping international law-making, shifting attention away from girls and allowing them to slip into the shadows.

For example, the two cornerstone conventions on women’s and children’s rights — the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) — explicitly address “girls” a grand total of once. And while there are treaties that do address girls’ rights, these often frame girls in a negative light, not as persons full of potential but as victims of the same few issues.

“Right now, we can see that girls are essentially invisible in the international sphere, in international laws and policy documents,” says Anne-Sophie Lois, the UN Representative and Head of Office for Plan International’s United Nations Office in Geneva.

“That means their specific needs and barriers and context are left behind. They are falling into the cracks between the agendas of women’s and children’s rights.”

These gaps in language are what inspired Plan International to create the Girls’ Rights Platform and its Human Rights Database, in order to facilitate access to more robust terminology on girls’ rights, to safeguard negotiated achievements, and to improve legal language.

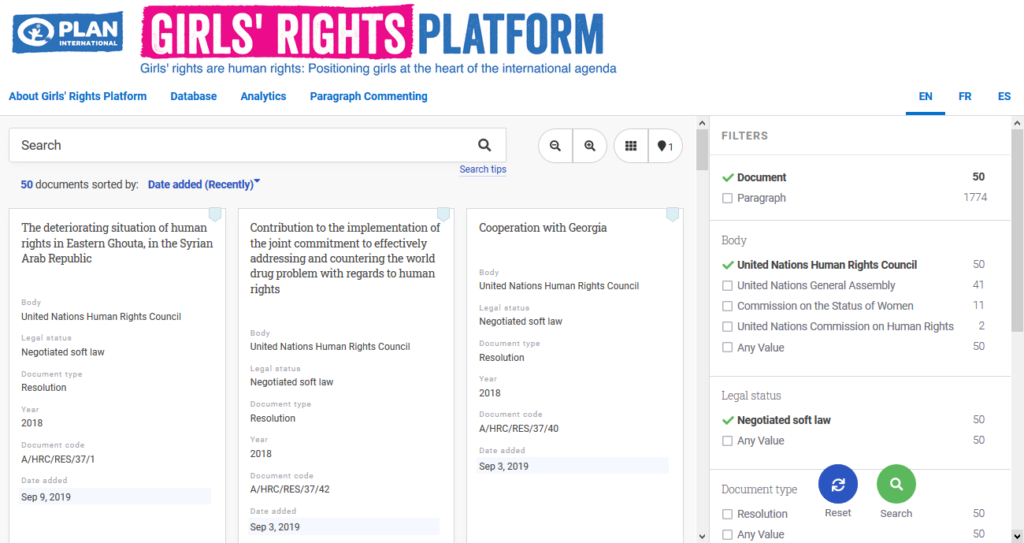

The database, which was relaunched in March 2020 with the help of HURIDOCS, is built on our web-based platform Uwazi. It offers easy access to 26,400 documents containing legally binding policy and soft law related to human rights across a wide variety of topics and three UN languages: English, French and Spanish.

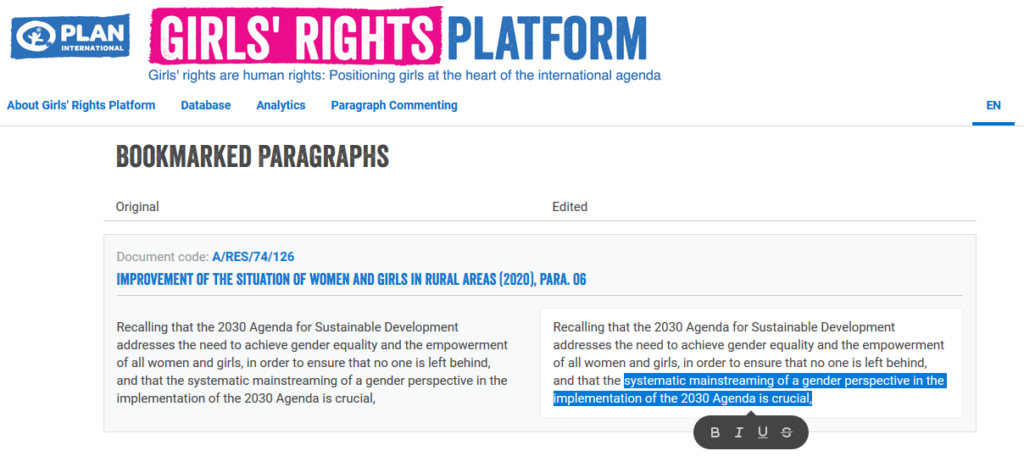

It also allows users to save and edit individual paragraphs. Why? Policy makers often use existing language as a starting point when negotiating new recommendations or conventions. The aim is to facilitate this work, as it represents a key piece in the puzzle of ensuring girls’ rights are included on the international agenda.

Machine learning for more efficient human rights work

Caring for a database is a labor-intensive job that can steal away hours from advocacy, so under the hood of the Human Rights Database are several improvements that make maintenance more sustainable for Plan International.

These in turn ensure a more up-to-date and well-organized collection for all the diplomats, experts and researchers who rely on it to access human rights law and policy.

One of the important changes is the addition of machine learning features, which automate tasks that in the past had to be performed manually.

For example, a member of Plan International’s staff previously had to keep an eye on the various policy making bodies, download any new documents that had been published, and upload them to the database. Now a smart bit of software systematically browses these sources and imports any new documents into the database automatically.

And whereas before a person had to read each document, break it down into paragraphs, categorize these by topic and persons affected, and annotate details such as countries involved, now specially trained algorithms speed up the process by making suggestions with a high degree of accuracy.

The person curating the database can accept, modify or reject the suggestions — thereby helping the algorithms to learn and improve their performance — and then decide if and when to publish.

“It’s really interesting to see how these technologies that are relatively new to the human rights world save so much precious time,” says Manushak Mila Guilhem, the HURIDOCS project manager for Plan International, “helping defenders focus their attention on the core of their work: advocacy and protection of human rights.”

These technological achievements are the fruit of a collaboration between HURIDOCS and a group of developers and product managers from Google.

In 2019, HURIDOCS was selected as a Google AI Impact Challenge grantee, which included the opportunity to take part in the Google.org Fellowship, a program that allows Google employees to do full-time pro bono work with a grantee for six months.

We at HURIDOCS have long been intrigued by the idea of using machine learning to facilitate access to public human rights information, which is too often scattered in several places and difficult to navigate. While we had taken preliminary steps to put the technology into practice, the Google.org fellows, with their fresh perspective and expert hand, helped us to advance this work by leaps and bounds.

“There is incredible potential for improving human rights by leveraging already agreed-upon standards and recommendations,” says Friedhelm Weinberg, HURIDOCS Executive Director. “With information made much more accessible, and in much more detail, to a greater number of advocates, we can use this potential to improve the daily lives of many people.”

“What do the users want and need?”

Not everything with the Human Rights Database relaunch came down to innovations of technology, but rather were the product of listening, learning and introspection.

As part of the process, members of the target audience of the database were interviewed about, among other things, how they go about searching for information when it comes to policy and decision making.

Additionally, all humans have biases. Training an algorithm to successfully complete a task meant that Plan International staff had to first interrogate why they preferred one approach over another.

As well, HURIDOCS practices agile software development, a method that emphasizes adaptability and iteration in the search for a solution. Although it has its benefits — and its drawbacks! — it can be a jarring experience for the uninitiated.

Not to mention, this was the first time that the HURIDOCS team worked on machine learning features beyond the confines of experimentation and research. In agile development, communicating expectations is critical, something we are constantly seeking to improve. Bring to the mix a new technology like machine learning, and it becomes doubly important to find ways to effectively convey possibilities and limitations, a challenge that we are continuing to explore.

“It was really a learning experience to run through an innovation project where the solution could change along the way,” says Anne-Sophie of Plan International. “We were forced to confront our assumptions and open ourselves to users and to listen to them: what do the users want and need?”

We’re only a decade away from 2030, the year identified by all UN member states as the target for achieving that “blueprint for peace and prosperity” known as the Sustainable Development Goals. The fifth goal? Gender equality for all women and girls.

There remains much to be done if gender equality and all of the other goals are to become a reality. However, if we can ensure that the legal frameworks meant to protect the fundamental rights of girls actually address the fundamental challenges that they face, we’ll be that much closer to a world where girls can live happy and healthy lives.

Do you curate a collection of human rights documents that could benefit from better technology? We at HURIDOCS would love to help. Get in touch!