“I worried that I would not make it out of there alive”, says Lee Young-joo, who spent three months in the Onsong Detention Centre in North Korea. Lee Young-joo tried to leave North Korea in search of a better life in 2007, but was captured in China and sent to Onsong Detention Centre where she awaited sentencing. Lee Young-joo is one of hundreds of detainees in North Korea subjected to daily ill-treatment and grave human rights violations, whose stories are now collected in a database for the very first time.

Compiling verifiable evidence in the North Korean Prison Database

Verified evidence is key for accountability and justice, irrespective of when it will occur. This is why Korea Future, a non-profit, non-governmental organisation working primarily from South Korea, has set out for an in-depth primary investigation of the North Korean penal system. It is the first of its kind and the crime-based evidence adheres to international law standards. With the support from HURIDOCS they have compiled the findings of the first phase of their investigation into Uwazi, our open-source flexible database application.

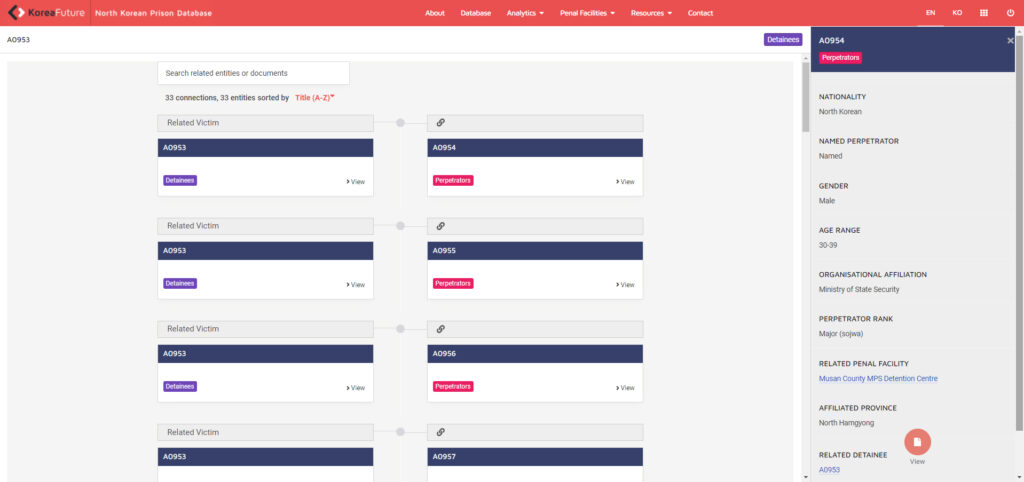

Through the use of Uwazi, the violations committed against detainees are presented in granular detail, with concrete linkages to perpetrators and facilities. It also presents the legal elements of every single documented violation of international law, including specific constituting acts.

“Using Uwazi, we have been able to simultaneously break down our raw data into granular details and track the broader patterns of violations. The recently revamped multi-inheritance function was especially helpful for identifying new patterns in an expedited fashion. In addition, we have been able to preserve important connections between our data points which are necessary for accountability. For instance, the relationship function enabled the linkage of perpetrators to their victims, penal facilities, and violations. These are just a few examples of ways Uwazi’s functionalities have allowed us to build a data model that will most benefit the legal and justice actors who will use our evidence for accountability.”

– Hae Ju Kang, Co-director at Korea Future

The public version of the North Korean Prison Database (NKPD) contains selected information that was gathered through 161 detailed in-person interviews. The private version of the database contains the full dataset including transcriptions of all 259 in-person interviews conducted. Korea Future will make the private archive available to international and national justice actors, journalists and researchers upon request. They interviewed individuals who are currently living in exile and include survivors, perpetrators, and witnesses who either experienced, witnessed, or committed violations of international human rights law in the North Korean penal system. Korea Future documented thousands of pages of transcribed testimony, sourced internal documents, gathered photographic evidence and obtained video evidence from inside North Korea.

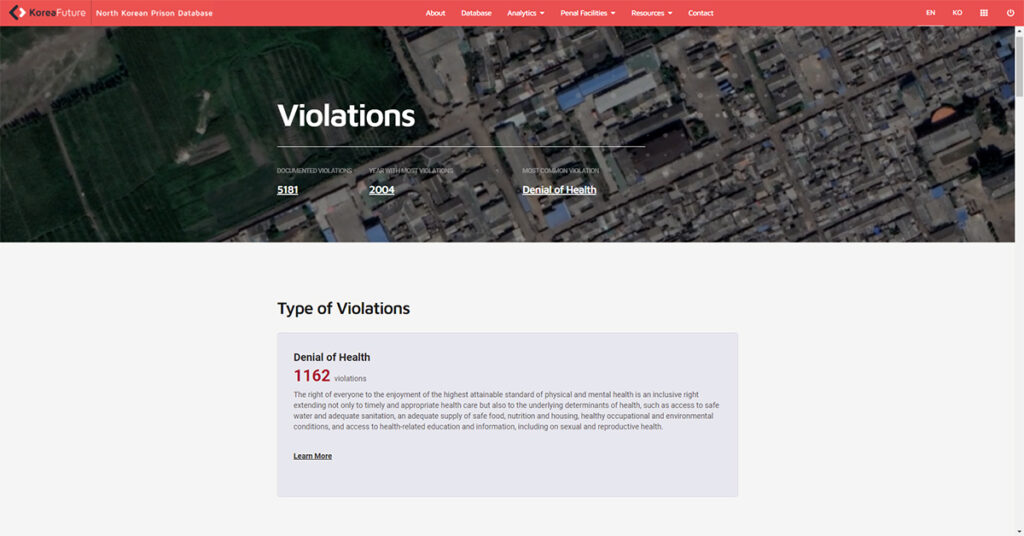

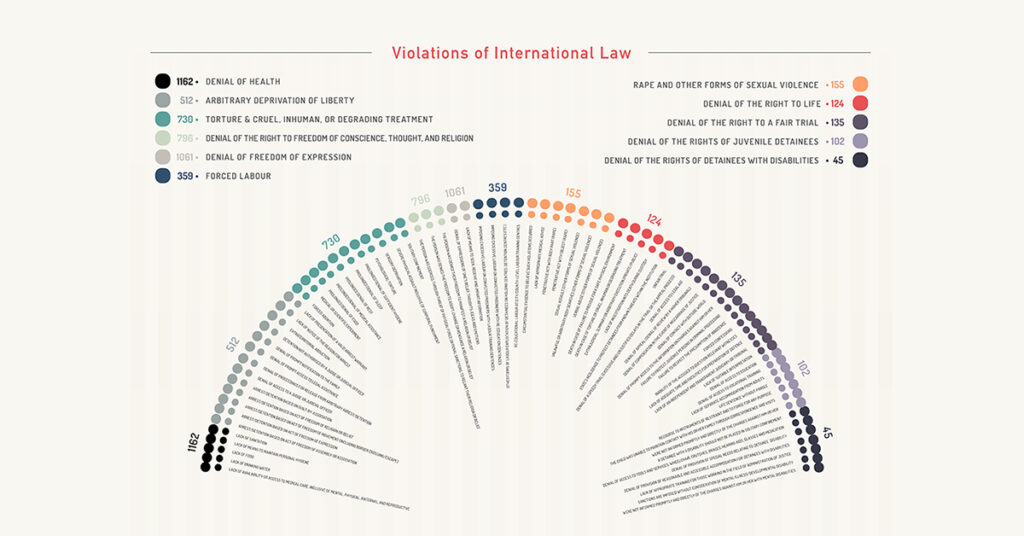

Up until March 2022 (which covers the first phase of their research) Korea Future identified 597 perpetrators linked to 5,181 human rights violations committed against 785 detainees in 148 penal facilities. Their methods of investigation were developed and reviewed by legal experts who have international prosecutorial and analytical experience. The evidence was then evaluated through a lens of international human rights law, customary international law, peremptory norms, and basic principles while they kept communications logs and chains of custody.

Widespread brutality in an isolated country

According to Korea Future, it is customary belief that those who are detained and brutalised in North Korean prisons are ‘political enemies’ of the North Korean government. Their investigation, however, finds that arbitrary mass detention and penal violence are inflicted on a wide range of detainees. This includes those convicted of common crimes such as theft and assault, as well as those who have tried to flee North Korea, engaged with South Korean individuals, or participated in religious or spiritual activities such as prayer. Not even the vulnerable, such as pregnant women, persons with disabilities or children are spared the fate of arbitrary detention, institutional violence and an overall denial of basic human rights.

Often referred to as the ‘hermit kingdom’, North Korea has for decades estranged itself from the international community and developed an extreme level of isolationism. The recent Covid-19 pandemic drove the country into even deeper isolation. The North Korean response to the pandemic is emblematic of the actions by the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea, led by Kim Jong Un: borders were closed, foreigners were banned, flights were halted. For one of the most repressive countries in the world, the North Korean response to the pandemic is beyond concerning. As a result of the pandemic and the resultant self-imposed closure of the country, the scope of the first phase of Korea Future’s investigation covers violations that occurred from 1997 to 2019 and testimonies were obtained from individuals that are in the diaspora.

Satellite imagery and digital modelling to support justice

The aim of the North Korean Prison Database and its accompanying report is to accelerate justice and accountability for victims of human rights violations. Korea Future hopes that by exposing the crimes committed in the penal system, which is backed-up by crime-based evidence, relevant stakeholders can use positive international law for actions to challenge impunity and international crimes.

What makes this database even more valuable for justice actors and those researching the North Korean penal system is the addition of satellite images. Korea Future supported the introduction of the satellite imagery function that is now available to use within Uwazi. “The satellite imagery function is key for end-users to understand the locations in which the human rights violations have occurred, “ says Hae Ju Kang, Co-director at Korea Future. “This function makes geolocations more concrete and enables the analysis of the specific facilities, which is a key part of our work.”

According to Natasha Todi, Project Officer at HURIDOCS, it required a lot of research and development to build the satellite map view for Uwazi, since the satellite imagery in North Korea has a lower resolution, as is the case for many Global South countries. “The NKPD is a great example where not only the process of building a database is important, but also the improvement of functionalities within platforms to highlight evidence appropriately.”

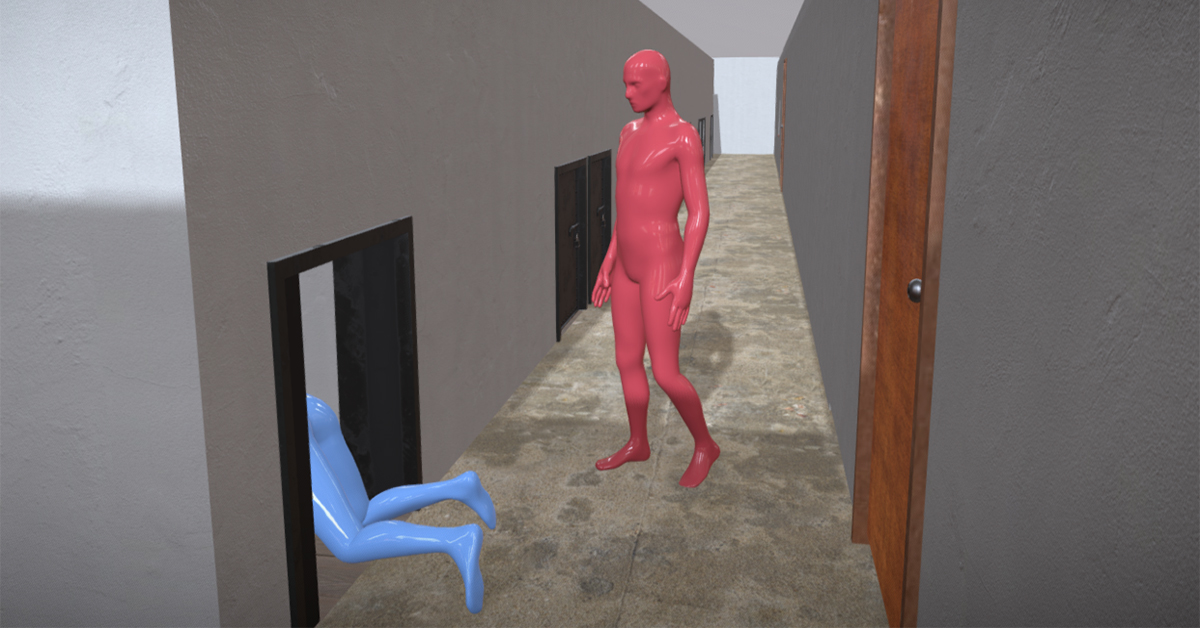

To further concretise the evidence, Korea Future used digital modelling, survivor testimony, memory-based diagrams, and satellite imagery to recreate the internal architecture of Onsong County MPS Detention Centre in the North Hamgyong province. This is the location where Lee Young-joo was detained, and is located less than one mile from the border with China. The detention centre covers approximately 560 square metres. To date, Korea Future has identified 24 individual perpetrators at this facility. Of these, 21 perpetrators have been named or partially named.

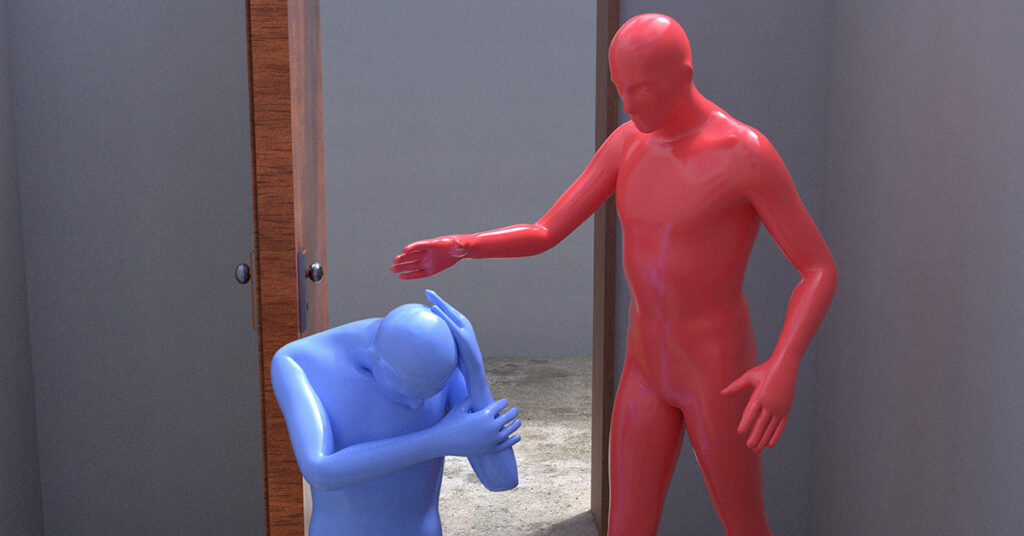

“Our 3D model shows the interior of a North Korean prison for the first time,” says Hae Ju Kang. The 3D model serves as a replica of the penal facility to demonstrate the internal architecture, and is a useful tool to illustrate the harsh prison conditions. In addition to scale, dimensions and layout, it shows how detainees are treated such as positional torture, where detainees are forced to sit crossed-legged without moving for hours on end. It also depicts how detainees endure degrading treatment such as being forced to crawl backwards when entering and exiting the prison cells, since they are not allowed to look at security personnel.

The detainees: Ms. Kim, Ms. Lee, Ms. Choi and Ms. Yang

The evidence collected by Korea Future reveals that North Korean penal facilities permit some of the most extensive and egregious violations of international law, with catastrophic consequences. Read the stories of Ms. Kim, Ms. Lee, Ms. Choi and Ms. Yang, as highlighted in the database and its accompanying report:

Ms. Kim

Ms. Kim (Detainee A0001) was incarcerated for more than 51 months at North Korea’s Onsong County MPS and MSS Detention Centres after being charged with the crime of ‘illegal international communications’. She was subjected to arbitrary arrest, denial of legal support and due processes, denial of food, positional torure, beatings, denial of rest, unsanitary conditions, denial of medical assistance, limited access to drinking water, denial of sufficient hygiene, denial of freedom of expression and denial of the right to freedom of conscience, thought, and religion. She witnessed a fellow detainee being tried and sentenced for 8 years for the crime of religious practice.

Ms. Lee

“How are you still alive?” asked a guard of Ms. Lee (Detainee A0953), who was held at North Hamgyong Provincial MSS Detention Centre. Ms. Lee was sentenced to 5 and a half years for exercising her right to freedom of expression. During her detention, she was subjected to intentional infliction of severe physical pain and suffering, psychological torture, and the prolonged denial of food, medical assistance, rest and sleep, as well as the prolonged denial of sufficient hygiene. “I weighed 32 kilograms when I was released from detention. I could even see my bones when I held my hands to the sun. I was only a thin layer of skin and bones”, said Ms. Lee upon her release.

Ms. Choi

For almost two years, Ms. Choi (Detainee A0909) was subjected to 12 hours of forced labour per day at the Chongori Re-education Camp. She was suffering from malnourishment, endured numerous accounts of harsh physical violence and was deprived of food, water, medical assistance, sanitation and hygiene. Detainees are often punished by reducing daily food rations, and like many female detainees, Ms. Choi’s suffered from amenorrhea as her menstrual cycle stopped because of malnourishment.

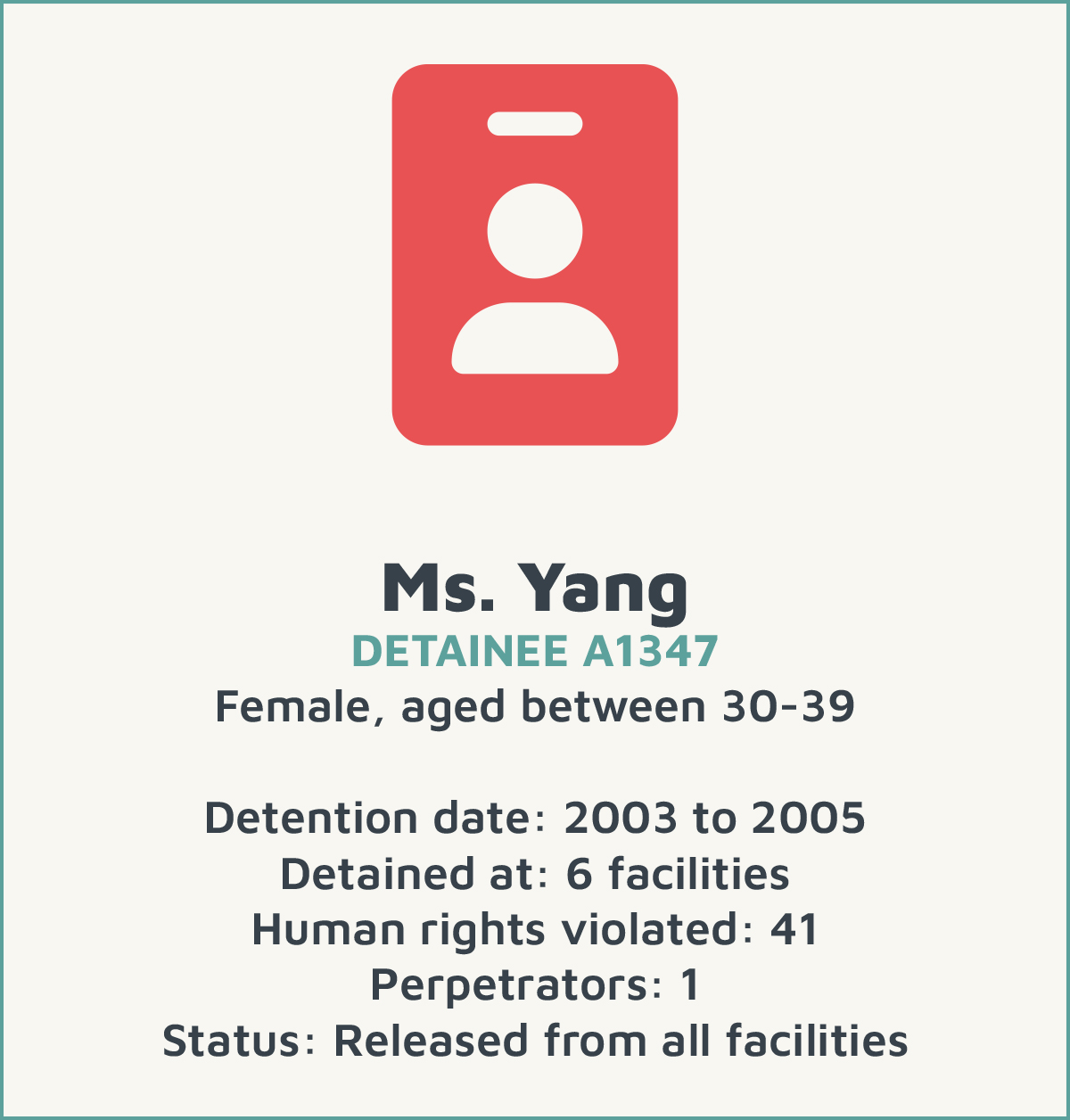

Ms. Yang

On two separate occasions, Ms. Yang (Detainee A1347) was arrested and detained at North Hamgyong Provincial MPS Holding Centre after being refouled from China. In addition to arbitrary deprivation of liberty, Ms. Yang was subjected to torture and cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment. In her testimony, Ms. Yang recalls being beaten “mercilessly with the most painful wooden sticks” and was only able to see the bruises on her face when she saw her reflection in a puddle of her own urine (there are no mirrors in the facility). She also suffered from prolonged denial of food, medical assistance, and rest and sleep, as well as the prolonged denial of sufficient hygiene when she was detained.

Justice will happen

The testimonies from Ms. Kim, Ms. Lee, Ms. Choi, Ms. Yang and more than 700 hundred other detainees are collected in the North Korean Prison Database to highlight the systemic and systematic abuse of human rights in the country’s prisons. Even though there are many more stories not yet told, Korea Future endeavours that the testimonies they have collected so far can be used by various actors to expose the abuses and be acted upon.

As a result of their findings, they make a number of recommendations and call on the international community, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and the United Nations Security Council to ensure that these violations of international law are addressed so that human suffering can end, future abuses be deterred, perpetrators be prosecuted, and that justice and accountability can be achieved.

“We are not lawyers, we are investigators,” says Suyeon Yoo, Korea Future’s Co-Director. “We are preparing the groundwork for future justice and accountability processes. We don’t know when it will happen, but we don’t doubt that one day, it will happen.”

Do you need to shape and share a collection of human rights information? HURIDOCS would love to help. Get in touch!