Women journalists today can find themselves at a dangerous junction of human rights abuses. As a recent report from the Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women explains, they are subject to discrimination and sexual harrassment in the workplace because of their gender and other intersecting identities, such as race and ethnicity.

At the same time, women journalists — just like their male colleagues — are targeted with smears and violence for their work holding powerful groups to account.

How to improve this distressing status quo? Among other things, the Special Rapporteur recommends that the world needs more verified information about these attacks. States could also support civil society in creating platforms that give early warning when conditions are ripe for violence.

Put simply, human rights abuses of women journalists must be brought out of the shadows. The Civil Association for Women’s Information and Communication (CIMAC) is well aware of this need. The Mexico-based organization has been documenting attacks on women journalists for 15 years — and has seen how the lack of information can impede recognition of the problem.

“Just being a woman can increase the potential of a situation to turn violent,” says Lucía Lagunes Huerta, the general director of CIMAC. “For us, being able to document and demonstrate it is essential.”

But evidence alone isn’t enough. For information to feed change, it must be made accessible to people who can act on it. Women journalists need the information that CIMAC collects in order to know how best to take care on the job. Others who have a role to play include state institutions with the power to enhance protections for women and journalists; male journalists, who could use their position to create more inclusive and safe spaces for their female colleagues; and the public at large, whose voices could join the clamor for progress.

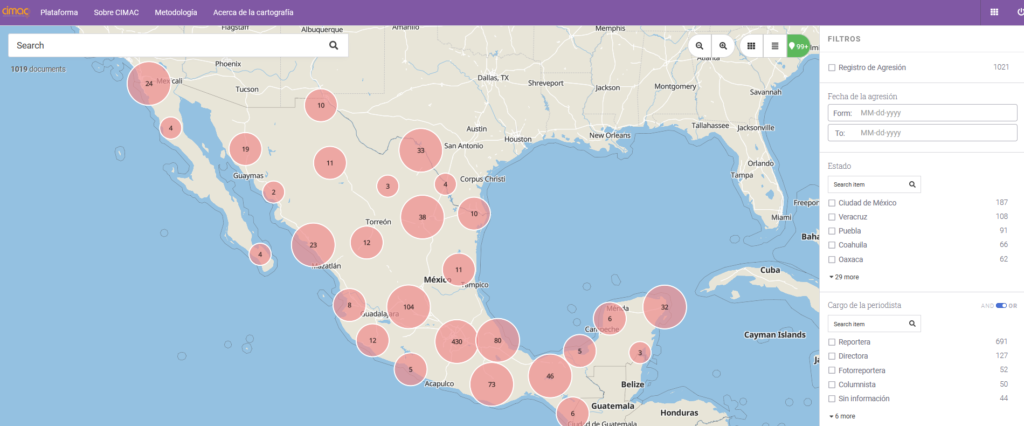

With all this in mind, last year CIMAC launched their Cartography of Attacks Against Women Journalists in Mexico, an online database that offers a comprehensive history of the dangers that women journalists have faced — and continue to face.

The cartography is built on Uwazi, our application for capturing and organizing collections of information. HURIDOCS collaborated with CIMAC to configure Uwazi to their specific needs.

Verifying and mapping cases of violence

The Spanish-language collection contains information on nearly 1,000 cases of violence against women journalists in Mexico since 2002. Entries can be viewed on a map, as cards, or in a table, and can be filtered in a number of ways, including:

- the Mexican state that the violence took place in;

- the topic that the journalist covered, from corruption and organized crime to environmental matters or social movements;

- the type of violence inflicted: physical, psychological, sexual, etc.;

- and the profile of the perpetrator, such as state- or federal-level civil servant, a labor union member or fellow media worker

The contents are the result of CIMAC’s documentation efforts on gender and press freedom. The organization receives tips about cases of violence from a national network of journalists that they’ve cultivated. They also monitor the press and social media for related news.

Whenever possible, CIMAC will then get in touch directly with the victim to learn more, conducting an initial interview and a risk analysis. They will attempt to verify the information with other sources like friends and colleagues of the victim, NGOs or security agencies. At the same time, they will investigate what action, if any, the relevant authorities are taking.

All of this forms the base for the Cartography of Attacks Against Women Journalists in Mexico.

“This violence based on our gender is used to limit our freedom of expression, used to hinder our journalistic work,” Lucía says. The cartography allows us to “continue to shed light on the situation of women journalists in specific regions.”

Systematically gathering the facts and making them available on Uwazi is just one part of CIMAC’s work, though. Staff will track the case, provide support for the victim, and generate public pressure in favor of a remedy. The information they collect will also inform capacity building initiatives like trainings and workshops that CIMAC organizes for women journalists.

Addressing the digital divide

For documenters, there’s no one-size-fits-all way to build a collection. Different human rights violations require different kinds of information — not only because of their different natures, but also because mechanisms for justice and accountability have specific requirements for information to be considered valid.

That’s why we’ve designed Uwazi to be a flexible tool. Even so, there’s plenty of insights that can be gleaned from one context and adapted for another. HURIDOCS advised CIMAC on how to set up their database, drawing important inspiration from the work of some of our partners who also capture human rights information and share it publicly.

“The cartography is a very important instrument to strengthen the journalist community and promote collaboration and solidarity in specific circumstances: pandemics, job insecurity, threats, killings,” says HURIDOCS programme officer Ximena Arrieta Borja. “The only way to resist in the face of adversity is as a community, exchanging experiences, knowledge and information.”

Flexibility, however, can mean a steep learning curve, and CIMAC staff say they found it challenging at times to get acquainted with the ins and outs of Uwazi. It’s a good reminder that we developers of human rights tools must take the time to create usage guides that are understandable for folks of all sorts of technical and linguistic backgrounds.

As such, we’re actively working to improve our Uwazi documentation, rewriting explanations to be more grounded. In the near future, we’ll also be revising the Spanish translation and then creating a French version too.

Beyond Uwazi, CIMAC staff say the experience also spoke to larger issues: the need to break down barriers that women face in acquiring literacy in data and technology, and the need for human rights defenders to engage a broader audience.

“We’ve seen that there is a digital divide that’s not just generational, but is also along gender lines,” says Adriana Ramírez Vanegas, who heads CIMAC’s Freedom of Expression and Gender program. “If we are unable to build up the evidence to…shed light on what is happening, we will have a difficult time accessing processes” of accountability.

“It’s taught us how we can create platforms with accessible and educational information.”

Do you need to shape and share a collection of human rights information? HURIDOCS would love to help. Get in touch!