| What is this? | Who is this for? | How was it created? |

| This resource is intended to help you determine the key questions you want your database to answer, based on your goals and user needs [Read more] | This resource is for human rights defenders who are documenting violations in their communities. [Read more] | This resource was created by human rights defenders. Anyone can suggest changes. Ideas that need some expansion are flagged with a sprout.🌱 [Read more] |

How to use this resource #

Whether you are monitoring human rights violations through media sources, or you have documented and collected testimonies that you want to organise in a database, you are certainly using specific terms to identify information on these events. Maybe you want to update your list of terms to enhance your understanding of an issue, or maybe you are stuck processing your information, you have a new project, a lot of dispersed information, and you don’t know what else you could try.

In any case, you have realised that terminology is important to your information needs. Maybe you and your team have started to have discussions around what terms you will use to organise, describe and identify your data. If this sounds like where you’re at, we think this resource will help you by providing guidance in identifying, gathering, and defining your controlled list of terms.

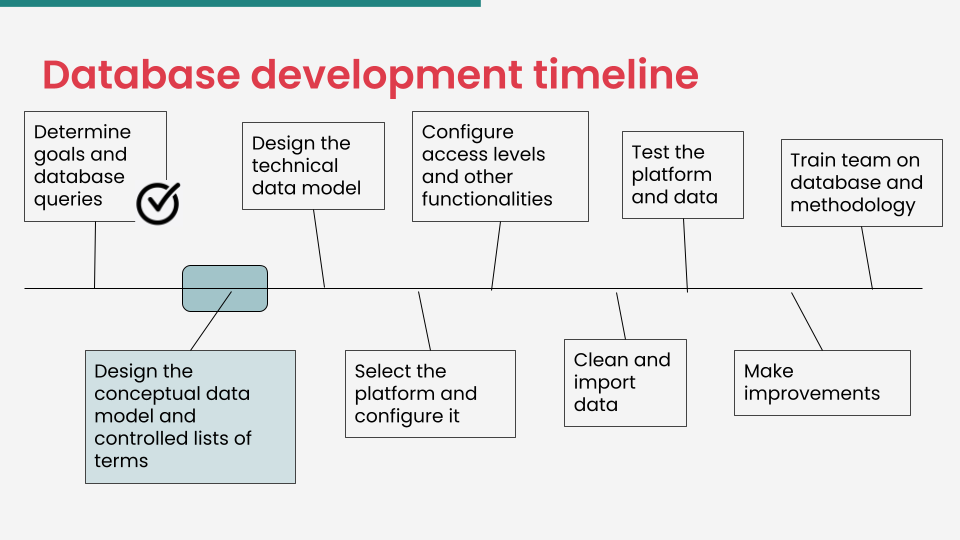

In the context of the database development timeline, you already have your information goals and database queries established, and you are now at the stage of designing the conceptual data model and determining your controlled lists of terms.

We begin this resource with an explanation of what a controlled list of terms is, why it is important, and the traits that a well-constructed controlled list of terms should have. Then we provide step-by-step guidance on how to go through this process.

We provide multiple examples throughout this resource – some hypothetical, and others from real-life organisations and projects, coming also from different fields (journalist deaths in South Sudan, police violence in the United States, etc.). We hope that these will help you understand the logic behind this work so that you can apply this to your own context and needs.

If you and your team already have experience with developing your controlled lists, but you are running into some problems, we hope you’ll find some new ideas in the challenges and advice section of this resource.

What is a controlled list of terms and why is it important? #

What is a controlled list of terms? #

A controlled list of terms is a list of words and phrases that will be used to index content and/or to retrieve content through browsing or searching. The meanings and uses of the terms in this list will be agreed-upon by your group so that you can catalogue and find information efficiently and consistently.

Your controlled list of terms will provide options for someone to choose from in order to catalogue (or label) a piece of information in your system. You will have a controlled list of terms for each attribute that is not a free-text field (a field in which it’s possible to enter any text). In practice, this list will consist of term options from which you can choose when recording information. Controlled lists serve as a reference for anyone involved in your database project to ensure consistent cataloguing and accurate interpretation of the data.

(Note: We use the term ‘cataloguer’ to mean the person whose role it is to catalogue the information.)

Why is a controlled list of terms important? #

A controlled list of terms is important for ensuring more consistency in the way your information is organised. By defining a specific list of terms, cataloguers will more likely select the most appropriate term for each piece of information in your system.

The cataloguer has a specific list of clearly defined terms from which to choose (as opposed to entering any words or phrases), thus reducing the likelihood of error. Consider how challenging it could be to keep systematic data on the districts in your country if each record is inputted directly into a free text field. This could result in hundreds of different spellings for the same district name. The data would inevitably become inconsistent, messy and impossible to manage, rendering it effectively meaningless.

For example, human rights defenders are documenting the killing of journalists throughout South Sudan. Three of the cities included in their investigation are:

- Juba city, located in Central Equatoria state

- Torit city, located in Eastern Equatoria state

- Bor city, located in Jonglei state

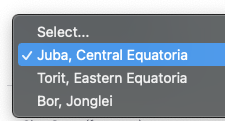

If controlled lists of terms are used to capture this information, it might look something like this:

When entering the location information:

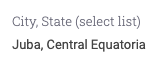

What you see as a result:

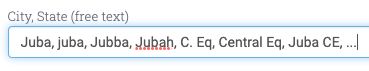

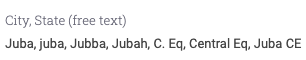

If there are no controlled lists, and instead the cataloguer is tasked with recording the location of the killing in a free text field, it might look something like this:

When entering the location information:

What you see as a result:

This example illustrates how it is much easier to control the consistency and accuracy of the information you record if you use controlled lists of terms. Where there are no agreed upon terms in place, the data can get convoluted and messy.

Term definitions should be made available not only to those whose role is to catalogue information but also to those who will retrieve the information so they understand the logic of the catalogue system.

Characteristics of a well-constructed controlled list #

In a well-constructed controlled list of terms, the following characteristics are considered and addressed:

- the terms list is exhaustive;

- terms are distinguished;

- terms are all exemplified;

- the terms are mutually exclusive;

- terms are equal in granularity or specificity; and

- terms are arranged alphabetically or in another logical order (Harpring and Baca, 2010).

We will explore each of these characteristics in more detail below with some examples of each. While each of these characteristics is applicable to a well-constructed controlled terms list, they are more easily achieved when you already have all of your data collected and ready for analysis. We recognise that, for human rights defenders, the process of data collection is often ongoing and ever changing, so achieving each of these characteristics may be challenging at any given time.

To demonstrate these characteristics throughout this resource, we will use the same example.

Characteristic: Exhaustive #

Your list of terms has to cover the spectrum of possible options in reality in such a way that we can always find a term to describe our entities. If we cannot find the appropriate term, it is time to either update the vocabulary or verify that we are actually describing the same entity.

Let’s suppose an organisation is monitoring the killing of journalists in their country. To catalogue information on this topic, the organisation will create a list of terms which they can reference to classify the types of killing that occur. They will include in their controlled terms lists every possible type of killing that is relevant to their investigation.

This list could look something like this:

| 1. Deliberate killing |

| 1.1 Extrajudicial execution |

| 1.2 Judicial execution |

| 1.3 Summary execution |

| 2. Indiscriminate/random killings |

| 2.1 Death as a result of being caught in crossfire |

| 2.2 Killing in demonstrations, crowd control and similar events |

| 2.3 Killing in indiscriminate attacks of such bombing |

| 3. Other unpremeditated killings |

| 3.1 Death as a consequence of torture or brutality |

| 3.2 Death from natural causes aggravated by the infliction of physical, psychological and sexual violations |

| 3.3 Death resulting from negligence |

| 3.4 Death resulting from intention to maim |

| 3.5 Killing of a wrong target |

| 4. Unexplained killings and deaths |

It’s important that this list is exhaustive in relation to the scope of their investigation because it will ensure their analysis is accurate and useful. Imagine, for instance, that the team decides not to include the term ‘Unexplained killings and deaths’ on their list and instead decide to include the option to select ‘Other’. When the time comes to analyse the information, the documenters may have to completely leave out any information about these types of killings or deaths because ‘Other’ could represent so many other options and could cause confusion. Alternatively, if there is no ‘Other’ option and the cataloguer is forced to select a term, they may select something that most closely fits with the event they are recording. This, however, could lead to inaccurate analyses or data that misrepresents the reality of the deaths of journalists. To ensure the accuracy of their data, the documenters need to include all possible violations on their controlled terms list.

Since their investigations are ongoing, it is possible that the scope of the information they collect may expand or shrink, thus shifting the exhaustiveness of the list.

If, in your work, you find that you keep needing to add terms to ensure your list is comprehensive in the types of violations it covers, then it will be helpful to create a process for evaluating and revising your terms list. We discuss this in further detail below.

Characteristic: Distinguished #

An important principle in determining appropriate lists of terms is to make sure that each term has an explicit characteristic that distinguishes it from all others in the controlled list. In other words, each term should be unique and different from all other terms. This characteristic is important because it will impact your ability to analyse your data. If the terms you are using are too similar, there is likely to be confusion at the point of coding the information (someone may select the wrong term when cataloguing a piece of information).

Our example organisation monitoring the killing of journalists demonstrates this characteristic well. Take, for example, the first section of this terms list:

1. Deliberate killing

1.1 Extrajudicial execution

1.2 Judicial execution

1.3 Summary execution

Although all of the terms in this section list relate to the same type of violation, namely ‘Deliberate killing’, all are distinguishable by a critical element. An ‘Extrajudicial execution’ refers to killings committed by state authorities outside the judicial or legal process, whereas a ‘Summary execution’ is the instantaneous deprivation of life as a result of a sentence imposed by the means of a summary procedure, in which the due process guarantees are not respected. A ‘ Judicial execution’ is distinguished from these other types of violations in that it is a killing commissioned by state authorities within the judicial process within which guarantees of due process are respected.

Characteristic: Exemplified #

Each definition should be accompanied by examples showing how to apply the definition in specific situations, drawing on examples from your existing information. Following on our example or case, exemplification could look something like this:

1. Deliberate killing

1.1 Extrajudicial execution: a journalist is executed by state officers with no judicial process observed at all

1.2 Judicial execution: a journalist is killed by the state as a result of being sentenced to death in a court with a just trial

1.3 Summary execution: a journalist is executed after sentencing by a kangaroo court (an illegitimate court in which the principles of law and justice are disregarded)

The process of ensuring that each of the terms on your list is paired with a real world example will help to limit the scope of this list, while also ensuring that it captures all the vital elements in your collected data.

Characteristic: Mutually exclusive #

In your terms list, each term must be mutually exclusive. Mutually exclusive is a statistical term describing two or more events that cannot happen simultaneously. Applying this concept to a controlled list of terms relating to human rights violations, this means that no single violation should fall under the definitions of two or more terms that define the single type of violation. This characteristic is closely related to your terms being distinguished, but it has to do more with the way in which you categorise your terms than the definitions themselves. So while each term definition must contain a unique element which distinguishes it from all others, so too should every violation be able to fit under one of these definitions and not two or more.

When we take our example of the organisation classifying types of killings of journalists, no single violation or act of killing could fall under two of the terms in the controlled list of terms. By establishing clear definitions for each possible type of violation, this organisation is able to more effectively analyse the killing of journalists in their country and shape their advocacy strategy.

Sometimes, there are situations where it does make sense that more than one term in a list is selected. When this is the case, it is important to create and document rules for how to use these terms.

📓 Berkeley Copwatch offers another example of rules to address potential overlap. Because there was a potential overlap between two terms (a person could be both the ‘Complainant’ and the ‘Subject’ of the incident) for ‘Participant Role in Incident’, their documentation offers instructions on the appropriate term to use (Berkeley Copwatch’s Data Dictionary + Controlled Vocabulary). For the term ‘Complainant’ they write the definition and the rule: A person alleging police misconduct or crime happened and is pursuing further action. (Can be the same as subject of the stop, although the cataloguer should select ‘Subject’ if this is the case).

Characteristic: Terms are equal in granularity or specificity #

Granularity in this context refers to the level of detail in a data structure. All of the terms in your controlled list must be equal in their level of detail.

If, for example, you are identifying forced displacements in South Sudan, you might want to obtain, at the very least, information on municipalities where those events occured. So, if you only found information about the state where an event occurred, but not municipalities (your regular standard), you will know you need to dive deeper to get all of the events to the same level of granularity.

Here is a simple example to demonstrate this concept:

| Terms equal in granularity (city, state, country) | Terms not equal in granularity |

| Juba, Central Equatoria, South Sudan Torit, Eastern Equatoria, South Sudan Bor, Jonglei, South Sudan | Eastern Equatoria Torit Jonglei |

Where granularity is concerned with depth, or level of detail of a term, specificity is concerned with scope (StackExchange, 2012).

Following with the previous example, suppose you want to identify the cause of displacements in South Sudan. Based on your information, you could see many potential causes (and terms) such as: ‘Massacre’, ‘Droughts’, ‘Natural hazards’, ‘Threats’, ‘Social leader killing’ and ‘Environmental causes’. In this case, you would need to organise your terms to ensure they are at the same level of specificity too. Terms from the above list that are equal in specificity are: ‘Massacre’, ‘Droughts’, ‘Threats’ and ‘Social leader killing’. If you are to include ‘Environmental causes’ you would be changing the scope of your terms since ‘Environmental causes’ is an umbrella term for more specific terms such as droughts and natural hazards.

| Terms equal in specificity | Terms not equal in specificity |

| Droughts Floods Massacre Threats Social leader killing | Droughts Natural hazards Massacre Environmental causes |

Characteristic: Terms are arranged alphabetically or in another logical order #

In the Berkeley Copwatch example, the terms are listed alphabetically, making it easier for someone to find what they are looking for. For time-related terms, you may want to order the list from oldest to earliest (or vice versa).

Note: There may also be situations that will require a more complex controlled vocabulary (with relationships and synonyms) instead of a simple controlled list of terms. We will not cover these more complex situations in this resource, but we hope to develop this guidance in the future. In the meantime, there are resources such as this to explore.

A process for determining your controlled list of terms #

The steps listed below have been generalised to fit most contexts. To see how these steps were applied to an actual project, please read our case study titled Determining your controlled vocabulary: lessons from WITNESS & Berkeley Copwatch.

Step 1: Clarify the lists of terms you will need #

Before diving into compiling term lists, first review and clarify the lists of terms you will need. In the section of this library called Designing your conceptual data model, you were guided through the process of determining your entities, attributes and relationships that form your conceptual data model. You will have a controlled list of terms anytime you have a specific trait (not a free-text field) for each attribute you’ve identified.

If you haven’t gone through this process of determining your conceptual data model, please go back to this guide and follow the steps: Designing your conceptual data model. Then come back to this spot and continue with this process.

Step 2: Plan your process #

Now that you have clarified the lists of terms you will need, you will plan out your process for gathering, defining and revising your term lists. Here are some questions to ask yourself and your team, as you look at the lists you need to gather terms for: What expertise will you need to define these terms?

For example, if your goal is to identify perpetrators, military units, and chains of command, you might need a political analyst, or someone from the social sciences with a strong background in these issues. There are also public resources that may support your work, such as the WhoWasInCommand database. However, if you want to add more/most substantive classification in human rights (e.g. ‘torture’, ‘extrajudicial killing’, ‘war crime of murder’), a lawyer will be necessary to ensure that your definitions are matching what the law says, because this requires legal input.

Who is responsible for what?

Who will own these lists as well as the process of maintenance and managing changes over time? Who will be responsible for maintaining the integrity of the lists? Who is responsible for documenting this process? Will this person require further training? Is this person able to train others?

How are decisions made?

How does this person systematise where definitions are being pulled from? How does this person take decisions on what to include or exclude from the list? Define a process for decision-making with your team.

How will you manage changes to these lists over time?

What will this process look like?

Step 3: Organise and define your terms #

Now it’s time to gather the terms you need to provide clear answers to your research questions. As you begin the process, it is a natural step to also begin drafting a definition of each term in order to differentiate them from each other. Eventually, you will want to consult with your team or the broader organisation to ensure that the definitions going into your controlled lists are understood by all.

There are two main approaches to finding these terms and/or their definitions: use terms from published sources (e.g. standardised glossaries or vocabularies), or define your team’s terminology that is based in the specific context within which you are working.

Using terms from published sources #

When possible and appropriate, controlled lists should be derived from larger published standard vocabularies. In the human rights field, there are glossaries created by specialised organisations that can provide a good starting point for your own controlled lists of terms. You might review the vocabularies used by organisations working on an issue comparable to your own.

Resources:

- Existing glossaries related to documenting human rights violations

- List of documented methodologies for databases of human rights violations

📓 For some of their term definitions, Berkeley Copwatch drew from existing legal standards for policing in Berkeley, CA (Berkeley Copwatch’s Data Dictionary + Controlled Vocabulary). For example, terms describing the ‘Use of Force’ by police (e.g. armoured vehicle, baton, canine, flash bang, handgun) use definitions employed by the Berkeley Police Department.

Define your team’s terminology #

If you decide not to use an existing published list of terms, then reflect on the terms your organisation is already using. Are there terms that you regularly use but do not have a written definition? Are there terms you use interchangeably that might confuse those outside (or inside!) of your organisation?

Take a look at your existing records to extract a draft list of the terms you currently use in your work, even if they are not standardised.

Document and clarify these existing terms as much as possible. Then put in place a process for a group of people to review these terms. This review will look at how the terms are used, and where there are problems or gaps (with specific examples). Ideally, this will provide the foundation for a discussion among the team on what needs to change regarding these terms and why.

📓 To determine what the controlled list of terms would be to describe the ‘Participant Role in Incident’, the Berkeley Copwatch team drew on their past experiences with participants in police interactions and estimated what potential roles participants and bystanders might occupy. In this way, the terms below were selected based on the experiences of the Berkeley Copwatch team and volunteers.

Similarly, terms describing the ‘Result of Stop’ (e.g. arrest, citation, injury/death, property confiscation) use definitions developed based on the experiences and observations of the police watch group (Berkeley Copwatch’s Data Dictionary + Controlled Vocabulary).

🌱 We want to include an example of this review process – please get in touch if you want to share more about your process for reviewing your controlled terms list!

Step 4: Test your terms #

Now that you have gathered a list of terms, you will test the terminology against a relevant sample of your existing documentation records. This step is important to verify that the data you collect fits under the predefined values you have laid out in your controlled terms list.

In practice, you should evaluate whether each attribute you have identified in your data model can be described by the terms on your controlled list of terms. If there are any attributes which cannot be identified by the terms on your list, then you may need to consider adding an additional term.

Your terms list also needs to make sense to those outside of your organisation who engage with the data you collect. You might want to keep in mind who the potential users of your database or information are and you can learn more on this by referring to this resource on determining your database user personas). Those outside of your organisation may understand or apply terms differently, so it is important to test whether the terms you have chosen to describe certain concepts in your data model can be understood by external stakeholders, in addition to your own team.

It is also important that all the cataloguers for your database agree with one another on what each term in the controlled list means, to ensure that everyone is applying them consistently to your information. To test this, you can conduct a simple exercise with your team.

✍🏾 Exercise: Let’s say that your organisation collects testimonies from witnesses about specific human rights violations. To test the terminology you have developed: Choose one or a few of the collected testimonies. Distribute them to your team of cataloguers. Ask each member of the team separately to identify the violations in that testimony according to your drafted controlled list of terms. Afterwards, come together to discuss where there was disagreement or uncertainty. From this discussion, return to your terms list to make adjustments, if required.

Step 5: Document your attributes, terms and definitions #

Now that you have tested your terms, you will document the attributes along with their definitions, the terms along with their definitions, and any rules to help guide someone responsible for cataloguing the information.

✍🏾 We have created this template in Google Drive that you can use or adapt to document your controlled lists of terms: Template for controlled list of terms.

This template is based on the Data Dictionary + Controlled Vocabulary by WITNESS and Berkeley Copwatch to accompany the People’s Database. The term is presented in alphabetical order in the first column, and the agreed-upon definition is presented in the second column, along with any rules or guidance for the person using these terms.

As much as possible, also try to document how and why you made decisions about terms, definitions or rules. Include decision points, where definitions are pulled from, etc. This step will enable you to maintain the consistency of your information, even as your controlled lists may adapt over time. This documentation will also make it much easier for colleagues and database users to learn your system.

📓 Once they had gathered their terms, the Berkeley Copwatch team refined, completed and documented them. The Data Dictionary + Controlled Vocabulary was created by WITNESS and Berkeley Copwatch to accompany the People’s Database. It serves as a reference for those utilising the database to understand what terms are held within and how these terms are defined.

By integrating the controlled vocabulary (including the lists of terms) into the data dictionary, WITNESS and Berkeley Copwatch made sure that all explanations of their data model and terms could be found in a central, accessible place. They distinguish the terms of the controlled vocabulary by highlighting them in bright yellow (Berkeley Copwatch’s Data Dictionary + Controlled Vocabulary).

Step 6: Revisit and revise #

Your lists of terms will change over time as the nature of your work changes. As the scope of your investigation shifts over time, so too will the terms you need to define for your database. However, you have created controlled lists of terms that should be easy to update and consistent in both scope (what is covered) and granularity (how deeply it is covered). To address the challenges that come with changes in the scope of your work, develop a process with your team or organisation through which you regularly revisit the controlled list of terms to ensure it still adequately captures your information and reflects the reality of your work. Document any changes made and the reason for adjustments in your records for future users.

Questions you may want to cover in your vocabulary review:

- Do any existing terms need to be more clearly defined?

- Do any new terms need to be defined?

- Do we need to apply specific rules to any elements?

Challenges and advice #

When definitions are difficult 🌱 #

There will be times when defining a term (whether that is a term from your list or the attribute itself) will be difficult. Your team will need to come up with a way to address this so that everyone will feel comfortable with it, but it doesn’t necessarily need to be the perfect solution. Instead, agree on the definitions and document your rationale for this decision, and any guidance on how to use the terms.

One example of terms that are difficult to define are those related to race. Berkeley Copwatch and WITNESS had many discussions on the definition of the ‘Race’ attribute itself. Their team settled on the term ‘Perceived race’ because the human rights defender has to guess the person’s race based on appearance. Information about the difficult definition and guidance on how to use this attribute is included in Berkeley Copwatch’s Data Dictionary + Controlled Vocabulary (page 66-67):

We acknowledge the complexity of race/ethnicity identification, and that we are, in many cases, basing our identification merely on perceptions. However, we feel that it is important to attempt to track these race/ethnicity categories.

See the concept of “Street Race-Gender”: A subjective approach to conceptualising categories of identity with the concept of “street race-gender”. The set of “meanings ascribed to a conglomeration of markers of physical appearance, including but not limited to skin colour, hair texture, facial features among other characteristics and interacting with gender.” (Lopez 2014)

The definitions listed below come from the U.S. Department of the Interior: https://www.doi.gov/pmb/eeo/directives/race-data

🌱 We know that there are many other contexts out there for which other examples of difficult-to-define-terms would be more relevant to human rights defenders. If you have an example of a term and/or list that was difficult to define, please get in contact with us so we can include a wide range of experiences and knowledge in this resource!

Advice on using the term ‘Other’ #

A common confusion is the appropriate usage of any kind of ‘Other’ category. You might choose to use the term ‘Other’ in cases where you face challenges to find specific information or when your list of terms is long enough for you to manage. However, you should be careful with this, because overusing this term could end up being the default for cataloguing information, preventing you from having good-quality databases and reports, and undermining the effort you have already done to define your other terms.

For example, if the information you are collecting is the ‘Country of origin’ and the terms are a long list of countries and ‘Other’, what does that mean? Does it mean that the person collecting the data didn’t know the right answer? Were they in international waters? Expatriates? Refugees? Is the country disputed territory and therefore not listed?

Or, imagine you are collecting information and trying to identify perpetrators in a country such as Colombia by using the term or category ‘Non-identified armed actor’. When gathering your information to write a report, you have 60% of your cases identified like this. By not distinguishing between specific armed actors (like Clan del Golfo, ELN, Los Rastrojos), you won’t be able to relate these events and actors to a specific territory, the kind of tactics they use, etc.

Therefore, it is important to discuss, decide and document what ‘Other’ (or any generic, related term) means in each context if it is important to allow for this option.

Advice on adapting and localising existing vocabularies 🌱 #

Using existing vocabularies is a lot easier than starting from scratch, but you need to think through how to adapt these terms to your context.

The terms you use need to be meaningful to the situation you are documenting. In other words, it is important to ensure that your terms are contextually relevant. While human rights are universal, and every individual regardless of location has the right to enjoy them equally, there will be instances where terms related to violations of rights need to be tailored to the contextual needs of a country or locale.

For example, Justice for Journalists (JfJ) documents violations against journalists in Eastern Europe. Some of the violations are specific to that region, such as ‘Being charged with rehabilitation of nazism’. This is a good example of using terms that are contextually relevant.

Having said that, it is also important to keep in mind that the language we use will reflect our particular vision of the world. As such, the terms we choose will reflect our particular outlook and biases. This is helpful in allowing human rights documenters to capture in their data the reality of the violations they investigate in a contextually relevant way. However, testing your controlled list of terms and receiving feedback from external stakeholders will allow you to ensure that the terms you use can be understood by those outside of your context, as well.

🪴 Help us improve this content by suggesting changes to this content via Google Docs!

References #

Patricia Harpring. Introduction to Controlled Vocabularies: Terminology for Art, Architecture, and Other Cultural Works. (2010). Last accessed January 27, 2022 from https://www.getty.edu/research/publications/electronic_publications/intro_controlled_vocab/

Profiling the Police: About the project: Accountability and transparency. Elgrito. (August 30, 2018). Last accessed January 27, 2022, from https://elgrito.witness.org/about-the-project/

The People’s Database for Community-based Police Accountability: A Berkeley Copwatch + WITNESS initiative. WITNESS Media Lab. (October 15, 2020). Last accessed January 27, 2022 from https://lab.witness.org/berkeley-copwatch-database/

Data Dictionary + Controlled Vocabulary. WITNESS and Berkeley Copwatch to accompany the People’s Database. (May 12, 2020). Last accessed January 27, 2022 from https://library.witness.org/product/data-dictionary-and-controlled-vocabulary/

StackExchange. (2012). Is the word “granular” a synonym for the word “specific”?. Last accessed February 2, 2022 https://english.stackexchange.com/questions/53266/is-the-word-granular-a-synonym-for-the-word-specific

Further Reading #

Patricia Harpring. Introduction to Controlled Vocabularies: Terminology for Art, Architecture, and Other Cultural Works. (2010). Last accessed January 27, 2022 from https://www.getty.edu/research/publications/electronic_publications/intro_controlled_vocab/

Fred Leise. Creating a Controlled Vocabulary. April 7, 2003. Last accessed December 11, 2021from https://boxesandarrows.com/creating-a-controlled-vocabulary/ Controlled Vocabulary: Hierarchical Classification, Thesauri, Taxonomy and Subject Heading Last accessed January 27, 2022 from https://www.controlledvocabulary.com/